By Alex Lantsberg, AICP, and Roxana Aslan.

CALIFORNIA is caught in a pair of traps affecting what kind of housing is built and where, and how it is produced. Together, they reinforce a dynamic of suppressed housing construction, unaffordability, and displacement. Policy makers are understandably focused on making it easier to issue permits for where the multifamily housing in California is needed. They must do more in that regard. Those same lawmakers must also consider the construction labor bottleneck that limits how many units can be produced. By anchoring housing permitting and financing policies around labor standards for construction, the state can facilitate the increased multifamily infill development it so desperately needs.

Despite an acrimonious housing debate, the “what and where” trap is the easier of the two to fix. Consumer preferences have shifted toward denser urban lifestyles, pushed along by policies to help adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change. Yet large portions of California metros’ high-demand transit-proximate areas are off limits to apartments. Where they are allowed, existing incentives tend to produce large, amenity-rich complexes. With land prices escalating, this often means that only the deepest pocketed builders can compete to deliver a luxury product to grab high-end demand. The market, however, has been unable to build enough of the housing in greatest need.

The state legislature has streamlined permitting for deed-restricted affordable housing and has eliminated some of the barriers faced by accessory dwelling units. These efforts, while laudable, are only down payments on the reforms needed to revitalize the housing construction market, and particularly to expand production of low and moderate income housing.

Loosening restrictions on apartment construction can help resolve this situation but will not address the “how” of production. For that, the state must intervene to fix a broken system that cannot fix itself.

Demand for homes is robust, but there are neither the contractors nor the construction workers to build them. Homebuilders’ low wages and poor labor standards make it difficult to attract new workers. Low pay in most private residential construction makes it a persistent challenge to keep skilled workers from leaving for better compensated commercial and public works construction. The resulting turnover makes it uneconomical for builders to invest in training to improve the productivity of the existing workforce. The most capable residential builders and workers gravitate to publicly subsidized projects with wage standards that largely avoid these dynamics. Neither does the coastal areas’ high cost of living make it economical for new firms, or workers from other regions, to move to California to fill the gaps. Without intervention, the production system remains stuck in low gear.

Integrating labor standards with policies to increase multifamily home construction will allow California to improve housing affordability by rebuilding its housing production system. This “high road” approach is based on paying workers wages sufficient to allow a dignified work and post-work life, supporting workforce development through apprentice training, and improving productivity by upgrading safety and skills. It would recreate the labor relations system in place during the state’s housing construction heyday from the 1950s through the 1980s when the California routinely produced between 200,000 and 300,000 units.

Labor needs

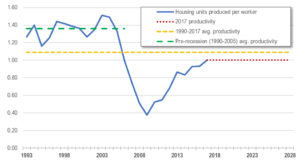

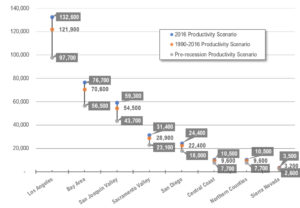

Meeting Governor Newsom’s goal of 3.5 million new homes in California in the next 10 years will require a massive increase in the rate of housing production to an average of 350,000 units per year. Building permit data show only 102,350 housing units authorized for 2016 and 114,780 for 2017. The number of units produced per worker, which was above 1.2 between 1990 and 2006, has not exceeded one unit per worker since then.

The labor required to meet the goal of 350,000 units is unlikely to be met whether productivity remains at its current levels or regains pre-recession levels. At its current production of roughly one housing unit per worker, California would need approximately 350,000 residential building construction workers per year — a workforce three times its current size and more than double its pre-recession peak. If productivity rebounds to pre-recession levels, nearly 140,000 more workers (approximately 257,000 total) will be needed.

Contractor shortage

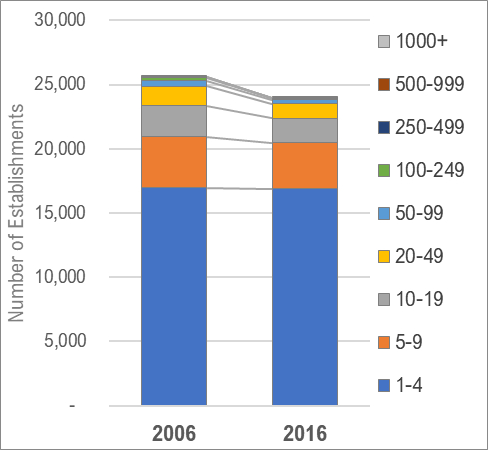

Discussion about the causes of the housing shortage has revolved around regulatory barriers to new multifamily supply, but few have focused on the construction industry’s capacity for housing production. After the Great Recession, the construction industry underwent significant changes that still constrain capacity. Many builders went bankrupt or reallocated their workers and resources. These contractors have yet to regain their previous form.

General contractors in the state have become smaller, and with fewer firms employing fewer people, construction capacity remains below its 2006 peak.

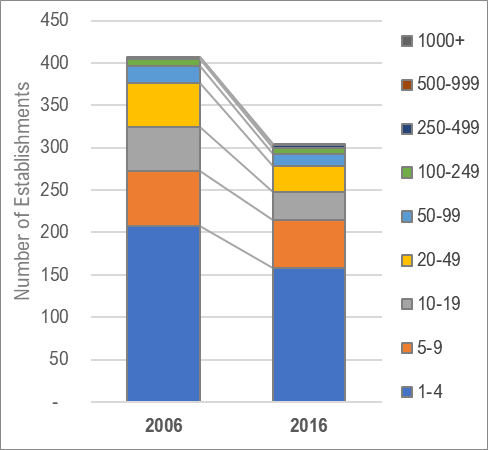

The residential construction industry has seen even greater declines. Current employment at multifamily residential general contractors is less than 80 percent of what it was a decade earlier, and the number of firms is down by more than a quarter.

The decline in housing construction employment in the state, while varying substantially by region, is linked to an even steeper decline in the number of multifamily general contractors; only the Bay Area reaches its 2006 level.

The decline in construction firm capacity correlates with the decline in housing production and indicates a serious capacity issue. Even in high-demand coastal areas the building industry is not large enough to ramp up production and provide the state with the new housing it requires. This has given builders immense pricing power that is contributing to unsustainable price increases.

Labor shortage

The tightening and consolidation of California’s contracting capacity is linked to the severe shortage of residential construction labor. Construction employment nationwide remains below pre-recession peaks — despite an improved economy and boost in construction — because the housing bust and subsequent recession displaced large numbers of construction workers, a majority of whom moved to other industries or left the formal labor market.

California’s construction labor market has generally followed national trends. Employment in nonresidential building construction returned to pre-recession levels by 2016, but employment in residential building construction remained about 37,000 workers short of its pre-recession peak.

The residential construction worker shortage is contemporaneous with the shortage of housing production across California. Housing production and residential construction employment both began to plateau around 2013.

This shortfall is undermining growth in the housing stock at a time when it needs to grow quickly to meet demand, particularly for thousands of families displaced by catastrophic wildfires in 2017 and 2018.

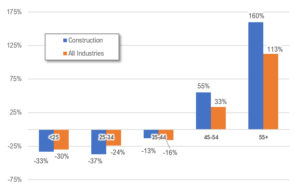

One factor is a decline in younger people in residential construction. The participation of workers under 25 has declined by nearly 40 percent since 1992, dropping from 13.4 percent of the workforce to 8.2 percent. The percent of hires in the 19–24 age group has declined from over 8.3 percent in 2005 to less than 7 percent by 2017, a drop of more than 16 percent. The graying of the construction workforce has exceeded the aging in the rest of California’s economy.

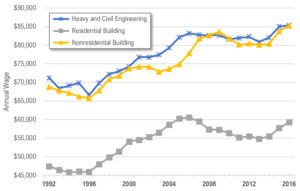

Historically, construction wages were comparable to those in manufacturing, while higher than many service sector jobs and the average private sector job. Today, US construction workers make less than they did 40 years ago. Examining annual pay for different construction sub-sectors since 1992, it is clear that residential building construction workers are generally paid less than similarly skilled workers in nonresidential and civil engineering construction. The lower wages appear to factor into the sluggish rate of housing production since the Great Recession.

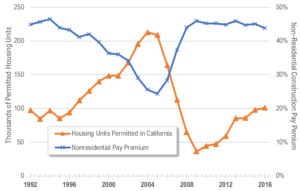

Looking at the pay differential in percentage terms makes its relationship with housing production clearer. Decreases in the gap between nonresidential and residential construction are associated with an increase in housing production.

Workers moving into construction generally received at least a 20 percent wage premium from their prior jobs. (Scott Littlehale, Jan. 2019) The residential sector fails to deliver such a premium.

Where to go from here

California can only solve its housing crisis by producing substantially more units in the right places, something that will require more workers and higher workforce productivity. But at current productivity levels, California’s residential construction workforce would need to triple to meet state housing goals.

Workers today have little incentive to join or stay in residential construction. Wages are stagnant – and benefit participation is declining – while opportunities are expanding in higher paying construction sub-sectors like public infrastructure. At the same time, residential builders are relying on an undertrained and underpaid workforce rather than on highly trained workers as they once did. Irrespective of land use regulations, these developers will be slow to build housing without a readily available pool of healthy, skilled, and dedicated construction workers.

As California proceeds to streamline the development process and incentivize residential density, it must also consider the workers — those who build the dwellings — by attaching prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements to procedural reforms. Because blue-collar wages and benefits comprise only about 15 percent of the total costs of a residential project, the impact on project costs is minimal and outweighed by the benefits of procedural streamlining and reduced parking requirements. Since prevailing wage regulations preclude contractors from cutting wages to win bids, they enable at least some construction workers to live in the homes and communities where they build. Apprenticeships will help attract people to the residential construction workforce by making residential construction a viable and sustainable career path. If the state through its policies can help rebuild its housing production system, California’s housing crisis may soon end.

Alex Lantsberg, AICP, is the San Francisco Electrical Construction Industry’s research and advocacy director. As a planner, researcher, and advocate, Lantsberg has worked on housing, labor, infrastructure, and sustainability issues in northern California for the past 16 years. He served on the APA California – Northern Section board as co-chair of the sustainability committee, 2015–2017. You can reach him at lantsberg@gmail.com

Alex Lantsberg, AICP, is the San Francisco Electrical Construction Industry’s research and advocacy director. As a planner, researcher, and advocate, Lantsberg has worked on housing, labor, infrastructure, and sustainability issues in northern California for the past 16 years. He served on the APA California – Northern Section board as co-chair of the sustainability committee, 2015–2017. You can reach him at lantsberg@gmail.com

Roxana Aslan is a Research Analyst with UNITE-HERE Local 11, which represents 30,000 workers in hotels, restaurants, airports, sports arenas, and convention centers in Southern California and Arizona. Her master’s degree from UCLA is in city/urban, community, and regional planning, with a specialization in community economic development and housing; and she holds a B.S. in environmental sciences and health from the University of Southern California.

Roxana Aslan is a Research Analyst with UNITE-HERE Local 11, which represents 30,000 workers in hotels, restaurants, airports, sports arenas, and convention centers in Southern California and Arizona. Her master’s degree from UCLA is in city/urban, community, and regional planning, with a specialization in community economic development and housing; and she holds a B.S. in environmental sciences and health from the University of Southern California.