By Georgia Sarkin, AICP, July 6, 2020

CITIES ARE THE CENTERS of creativity, capital, and connection. They are also at the front line of our current crises. The Covid-19 pandemic shut them down. Activity ceased with astonishing speed. Cities grew quiet. Mass protests over structural racism then swept through our streets and public spaces. Together, these twin crises have radically transformed our urban reality.

The global lockdown may be the single largest collective act that humanity has ever undertaken. A staggering 81 percent of the global workforce is affected. More than 47 million Americans filed for unemployment in 14 weeks. The people hardest hit were the most vulnerable: essential frontline workers, immigrants, the elderly, and communities of color. As a result, acute, underlying, longtime problems in cities have been brought into sharp focus. At the same time, we are being offered a glimpse of a future where the city could look quite different.

In thinking about how cities can evolve for the better after these crises, five factors affecting public space are crucial to consider — infrastructure, evolution, density, mobility, and equity.

Public Space is essential infrastructure

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s designs for New York’s Central Park, Chicago’s Jackson Park, and Boston’s Emerald Necklace testify to the powerful relationship among health, well-being, and accessible public open space.

The value of public space is being brought to light during this pandemic. In addition to its public health and environmental benefits, public space can reduce socioeconomic segregation, build trust, and reduce social isolation. The economic crisis brought upon by the pandemic is raising discussions about publicly funded infrastructure projects. It’s time that infrastructure be redefined and expanded to include public space.

Cities evolve after crises

Without the devastating outbreak of cholera in the 19th century, a new modern sewer system may not have been developed. The tuberculosis epidemic in New York in the early 20th century led to improved public transit systems and new housing regulations. The Great Fire of London in 1666 inspired the city’s first planning controls, including wider streets and thicker common walls between buildings to slow the spread of fire. If we want cities and our public spaces to emerge stronger from this crisis, city leaders, architects, and urban planners will need to think differently; indeed, many have started.

- In London, the Mayor’s Streetspace Plan will fast track the transformation of streets to enable millions more people to walk and bike safely.

- Bogota added 72 miles of bike lanes to its robust biking network.

- Oakland’s “slow streets” initiative will set aside up to 10 percent of the city’s streets for recreation.

- San Francisco has also launched a “slow streets” program.

Some cities are implementing new policies to guide future development.

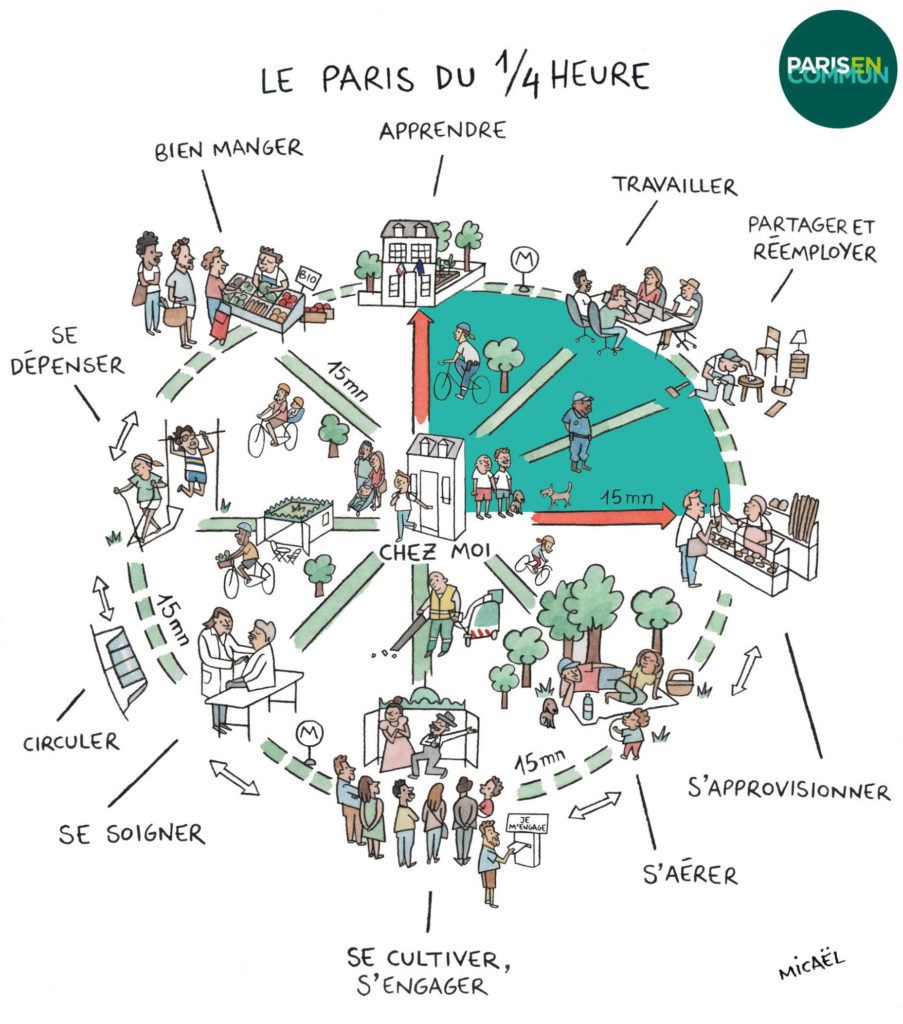

- Paris is aiming for a “15-minute city” with most daily needs a short walk, bike ride, or public transit stop away: The resulting self-sufficient communities would fulfill six social functions — “living, working, supplying, caring, learning, and enjoying.”

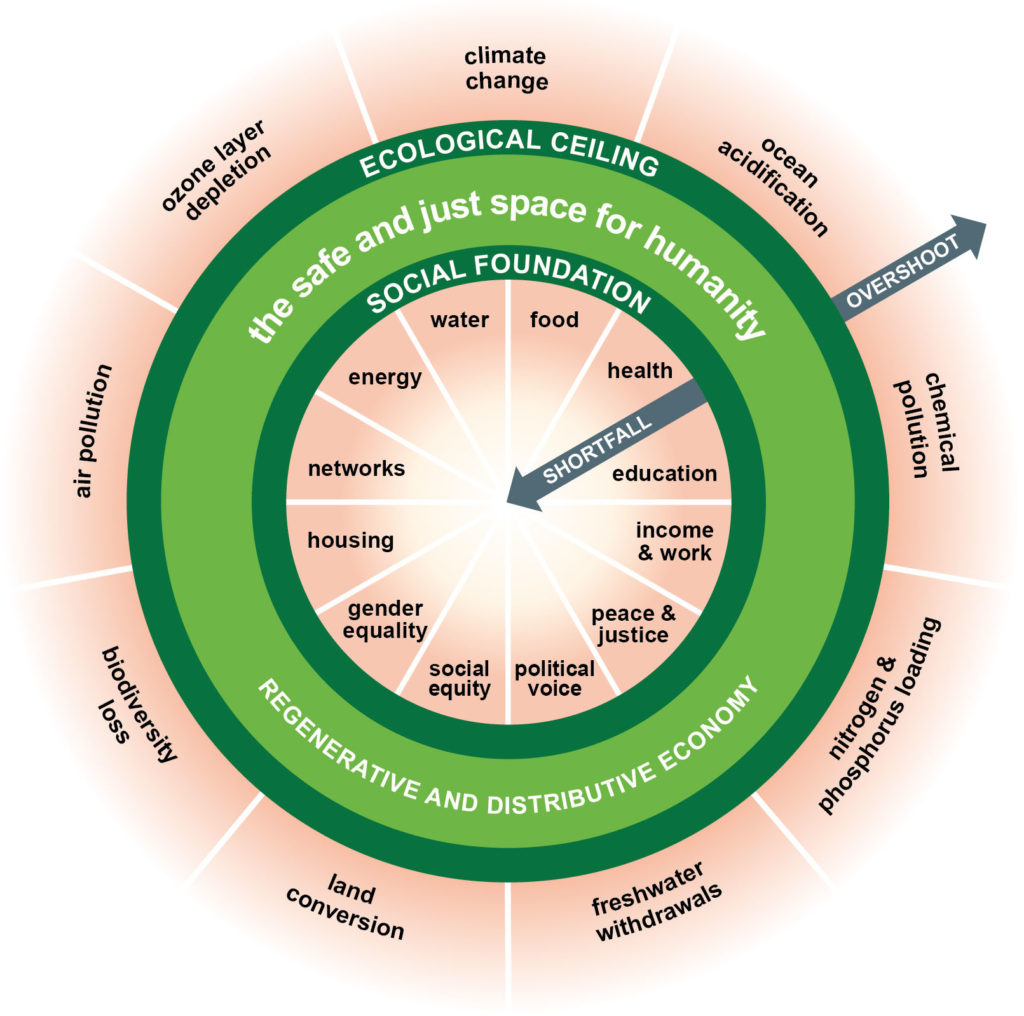

- Amsterdam has embraced a “doughnut” economic framework. The outer ring represents an ecological ceiling to avoid damaging our planet. The inner (“social foundation”) ring represents basic human needs. Anyone not reaching the minimum standards is living in the hole of the doughnut. This approach encourages policymakers and planners to look to the horizon.

- Singapore is paying attention to food security, as more than 90 percent of its food is imported. That country has been promoting urban farming with a goal to produce 30 percent of its nutritional needs locally by 2030.

But many city programs elsewhere are being implemented by discrete authorities or foundations, without coordination or a commitment to shared values. Spaces are being redesigned, roads are being closed, sidewalks widened, and civic spaces rethought. As cities move forward with reopening and beyond, we should seek to identify the fundamental values we share. Based on those, we can articulate shared goals and develop a clear, coordinated roadmap to realize them.

Density

Many writers, city leaders, residents, and government agencies are questioning urban density and linking a city’s vulnerability to the spread of pandemics. Perceptions that low-density areas are safer could draw people away from cities. This was the reaction after past pandemics. The modernist movement, for example, following closely after the Spanish Flu of 1918, raised similar concerns about density and its link to disease. As a result, utopian cities designed by modernist architects — such as Le Corbusier’s “City for Three Million People” — focused on providing space, light, and air. The drawings for these new cities — which influenced many aspects of modern urban planning — often depict huge expanses of open space devoid of people.

The view of many planners, architects, and urban dwellers in more recent times — influenced by Jane Jacobs, among others — is that dense compact neighborhoods and lively public spaces foster social cohesion and vibrant urban life.

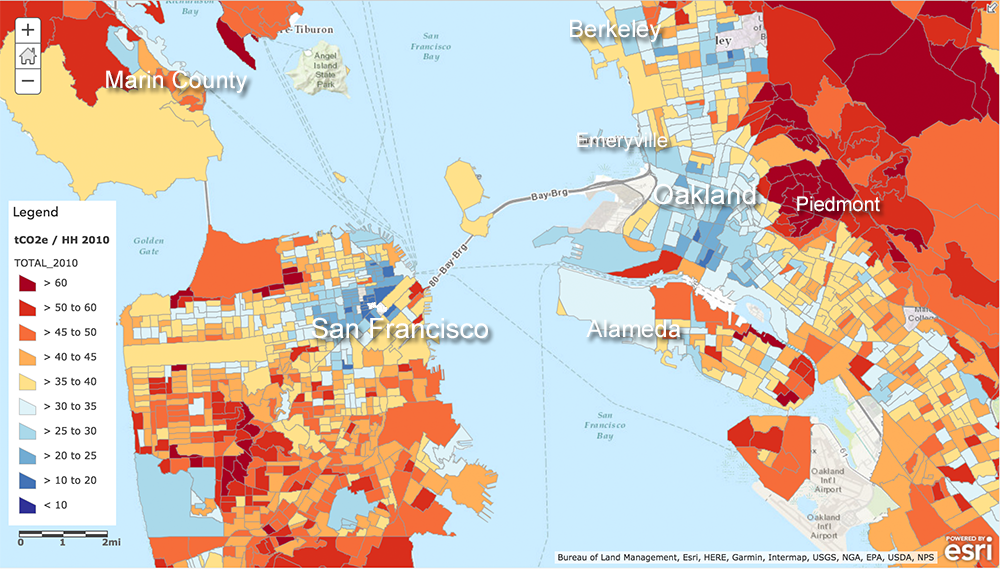

Denser cities are also more energy-efficient. On the map of the San Francisco Bay Area, the city centers (blue areas) have a much lower carbon footprint than outlying areas. Suburban sprawl cancels the carbon-footprint savings of dense urban cores. If lower density environments become more popular post-pandemic, they could have a significant, negative effect on climate change.

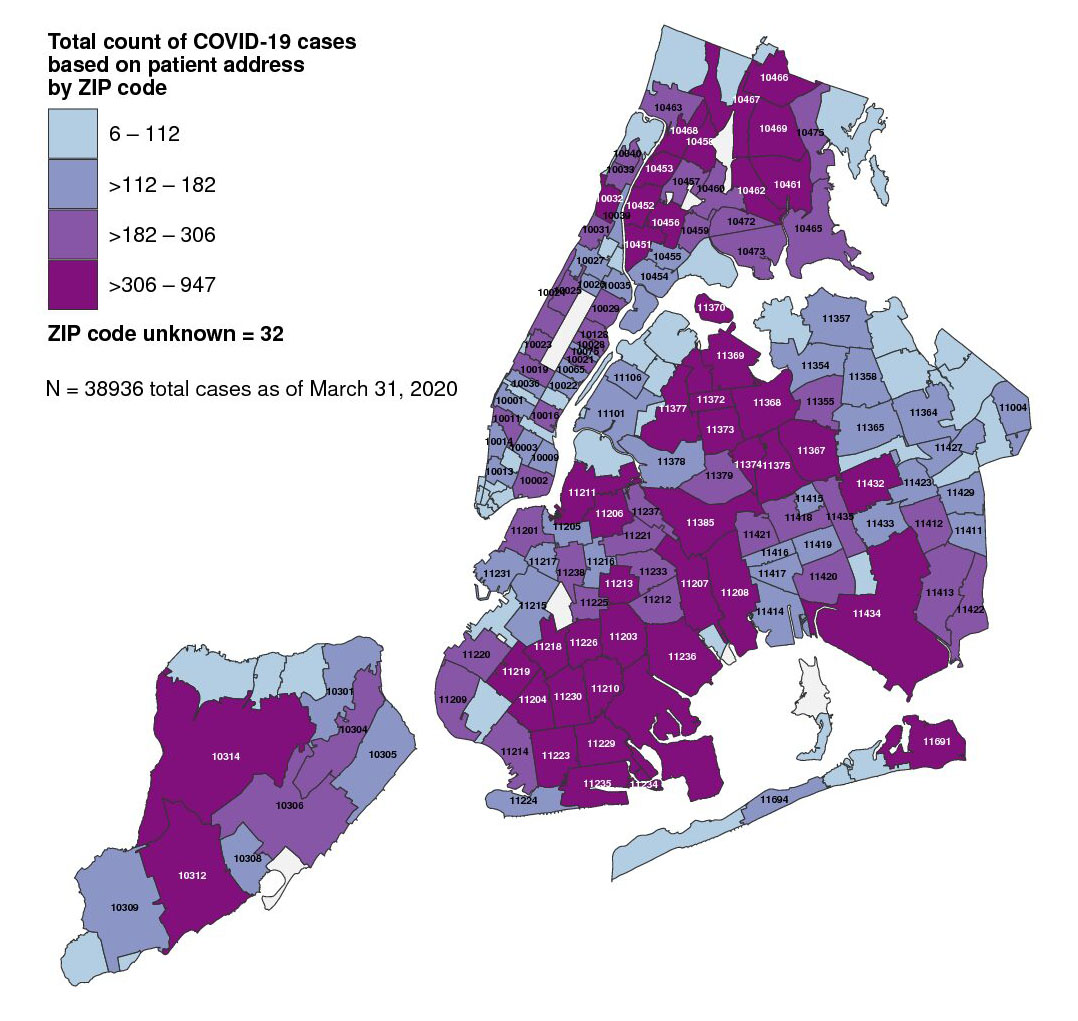

The correlation between density and vulnerability to the spread of disease also ignores the experiences of cities like New York, Singapore, Hong Kong, and cities in China. New York and Singapore have a similar density, upwards of 20,000 people per square mile. Yet Singapore’s well-managed initial outbreak was minimal in comparison to New York City’s. The geographic breakdown of the virus shows that Covid-19 hit hardest not in dense Manhattan but in the lower-density outer boroughs, like the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island with their lower-income populations, immigrants, frontline workers, and people of color.

Inequality is the problem we need to solve, not density.

Mobility

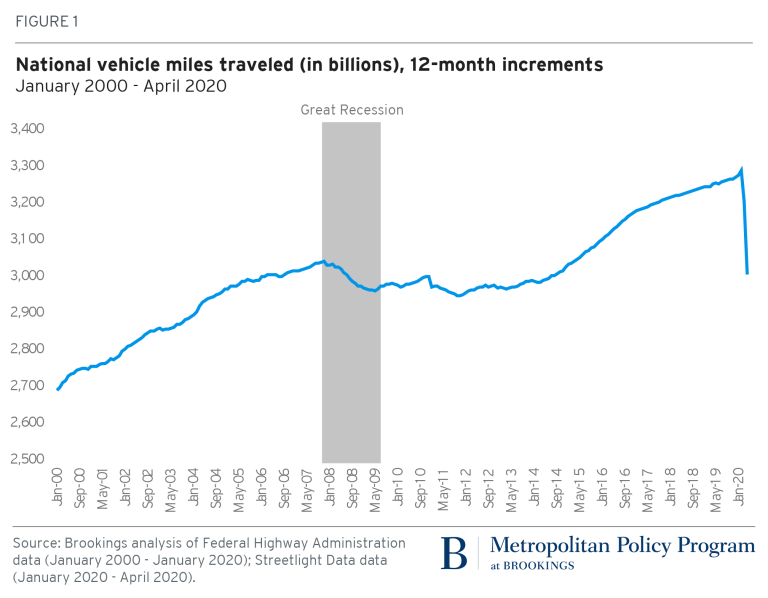

Traffic reduction is one of the few positive changes related to the tragedy of Covid-19. Empty roads have led to cleaner air, better views, and more space for outdoor recreation. National driving habits changed in less than two months. Never before, not even during the recession of 2008, have we seen a precipitous drop in Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) like the one seen between January and April 2020.

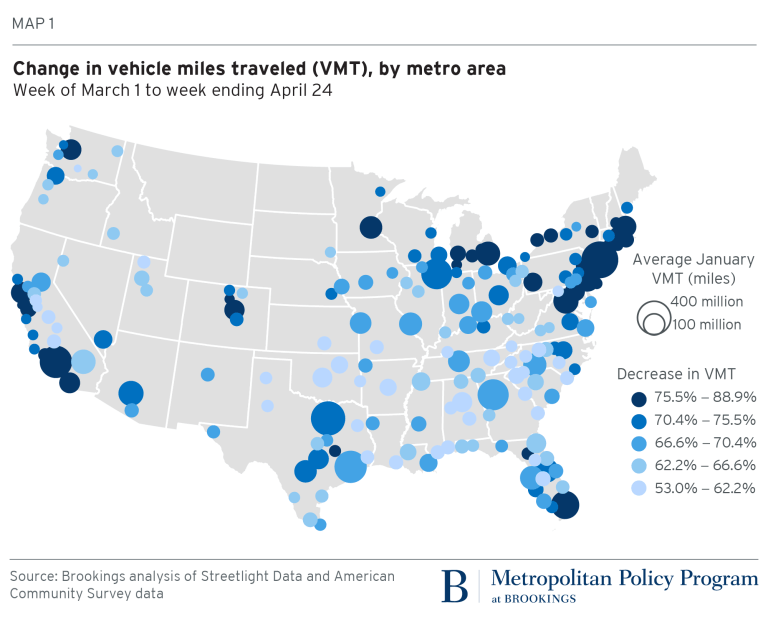

The drops in traffic are not restricted to dense coastal hubs. Most large metro areas saw traffic levels drop by at least 75 percent from March 1 to April 24, 2020. (Ibid, Map 1.)

It will be a big step back if cars become safe pods in which each of us isolates just to travel safely. Public transit could be redesigned with a focus on making buses, trains, and stations less crowded and safer. Demand for public transit will depend on reopening dates and people’s willingness to try.

Encouraging work from home, retrofitting roadways for biking, and expanding sidewalks for pedestrians should help transit systems experiment. In the short-term, transit hours and routing can be tried and tested. Berlin, for example, has shifted transit hours to align with workplace shifts, and has capped capacity at 50 percent. In the medium term, behavior patterns will change, necessitating new demand management strategies. In the longer term, city policies could incentivize decentralizing job centers, increasing mixed uses, encouraging flexible work schedules, working from home, and expanding and retrofitting transit systems.

Biking and walking increased in popularity during the lockdown. The pandemic has also exposed how streets are over-designed for private cars. This holds promise for redesigning streets to better suit pedestrians, cyclists, and public open space.

We have a unique opportunity to rethink transportation and mobility. Lockdown has enabled the country to undergo a transportation experiment at an almost unimaginable scale, and the lessons learned can be leveraged. If leaders take the right steps, we can emerge from the pandemic with a stronger and safer approach to mobility and improved open-space systems.

Metropolitan and state leaders should use the VMT data to target the communities that may be most willing to test new, post-coronavirus interventions and develop innovative and creative incentives for alternative forms of mobility. Reallocating space previously used by cars — especially in neighborhoods without walkable access to parks and essential services — would go a long way toward improving the public realm.

Equity

Our cities and public spaces provide platforms for civil liberties, freedom of speech, movement, and expression. They thrive on plurality and inclusiveness. Recent and continuing protests have highlighted the importance of inclusive public space for collective action.

The link between racism and public health has also become more evident. Black Americans face more health challenges than white Americans, including heart disease, infant mortality, and diabetes — underlying conditions that have exacerbated the impact of Covid-19 upon them. We need to focus on our underserved and put equity upfront in decision-making.

People in low-income neighborhoods often rely more heavily on accessible public spaces. Studies have shown that the percentage of green space in people’s living environment positively affects their general health. The public realm can, through open space and greenery, offer a path to social cohesion, healthy communities, and health equity. But neighborhoods also need easy access to good schools, healthcare, nutrition, transportation, and affordable housing.

As our cities slowly open after lockdown, contact tracing will help keep the virus in check; but we must be sure that anti-democratic, discriminatory surveillance practices will not also evolve. We have already seen sophisticated video surveillance in public spaces around the world. Spot, the “dog” is on patrol in Singapore parks, while a police robot in public spaces in Shenzhen warns people to wear masks and checks body temperature and identities. We may not have time to institute robust privacy laws if surveillance measures increase rapidly. The danger is that what we agree to do during an emergency may be normalized once the crisis has passed.

As we work towards a more equitable future, the participatory process is more important than ever. For public space to be relevant, we need to understand the relationship among people’s ways of life and their history, memory, and the built environment. We will need to focus on the public health benefits of space, give voice to marginalized communities, and spur our cities to repair past spatial injustices.

Seeing our cities through the lens of public health and equity has magnified the tremendous value of public space. It has also provided global momentum to make cities stronger, healthier, and more equitable for everyone.

Georgia Sarkin, AICP, RIBA, is an architect, urban designer, urban planner, and Principal with SmithGroup in San Francisco. This article (an

Georgia Sarkin, AICP, RIBA, is an architect, urban designer, urban planner, and Principal with SmithGroup in San Francisco. This article (an