By Leila Hakimizadeh, AICP, and John David Beutler, AICP. This article, a version of which was published in Strong Towns, September 24, 2020, presents the authors’ professional opinions, not those of their employers.

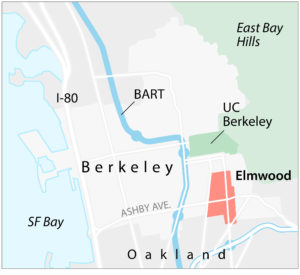

Elmwood is a fifteen-minute, tree-lined walk southwest of the campus of UC Berkeley. Centered on a two-block commercial street at the intersection of two-lane roads, Elmwood is filled with small apartment buildings, parks, and craftsman bungalows with flower-filled, water-efficient front yards. An irregular street grid links everything and offers views east to a row of hills and west to San Francisco Bay. While not short of college students, the area is a mix of families, the retired, rich, poor, and middle class. All support Elmwood’s restaurants, stores, shops, and the movie theater. The area has a school, a library, and a small hospital. Elmwood is a neighborhood.

Neighborhoods have become rare in much of the United States. Andrés Duany once told of a woman who informed him that she was interested in protecting her neighborhood. “No, ma’am,” he replied, “you live in a subdivision.” Indeed, most people outside core cities, in areas built after 1940, live in isolated, drive-to housing developments with businesses congregated around arterials. This is sprawl, reinforced by zoning, traffic engineering, retail practices, and social discrimination, and it has disrupted and hollowed out older mixed-use neighborhoods.

Yet the last few decades have seen, if not the end of sprawl, at least a strong rejoinder. Many cities and their neighborhoods have sprung back to life after years of official and unofficial neglect. Neighborhoods’ social, economic, and environmental advantages are being increasingly understood.

Covid-19 is a worldwide tragedy and creates urban challenges, but it will not be the end of cities. We have been here before. There will be long-term effects specific to neighborhood planning. The urban studies theorist Richard Florida predicts that we will continue to see one in five people working remotely. What will this mean for neighborhoods? How can planners, urban designers, officials, and developers create future neighborhoods to respond to the needs of tomorrow?

Neighborhood potential

The future of cities lies in their neighborhoods. More people will be around, more of the time, needing even more from their neighborhoods than before. What an incredible opportunity! In Elmwood, restaurants serve food to go and at outside tables (socially distanced), but post-pandemic, “working from home” will mean “working remotely,” not just “from home.” People will go back to the cafes, or for a long lunch at the corner restaurant, or to the office supplies store. The 24-hour neighborhood may once again be possible. As these local amenities flourish, the trend will be to walk for errands. To meet the neighborhood potential, we should move forward in five ways:

1. Develop equitable and socially just neighborhood plans

The pandemic has deepened social and economic gaps between our rich and poor neighborhoods. We must make an effort to rid them of decades of social injustice and inequity. Acknowledge many professions’ culpability in urban renewal, freeway location, and redlining. To create change in disadvantaged areas, engage backbone local organizations to understand peoples’ needs. Embed equity and inclusion principles, such as PHEAL, in neighborhood plans. Invite communities to work with us to write anti-displacement policies. Chicago uses Equitable Transit Oriented Development to prioritize investments in communities of color.

2. Practice place-keeping before placemaking

While working for positive change, recognize existing community patterns, public life, and the local ecosystem before undertaking neighborhood planning and placemaking. Place-keeping is preserving historic buildings and affordable housing and maintaining public spaces. It’s protecting cultural identity, sense of place, and belonging. How a community decides to maintain their way of life might be different from how we as urban planners imagine it for them. In neighborhoods of color, placemaking should enhance how a community uses its neighborhood based on analysis of existing patterns that represent the norms valued by residents. For example, see Restore Oakland, a model for repairing injustice, investing in economic opportunity, and restoring community safety.

3. Create new development compatible in built form, not density

To have enough users to support stores, parks, libraries, and public transit within walking distance, some neighborhoods will benefit from additional housing. However, new buildings much larger or different from existing ones can create fierce neighborhood opposition. In his recent book Missing Middle Housing, Dan Parolek recommends that planners and designers understand a neighborhood’s existing built form and scale before proposing new development. Moving codes away from measures like units per acre and minimum lot sizes toward a focus on compatible design will change the focus from density to urban form and allow us to bring in the missing middle housing that was common before the 1940s.

4. Create accessible open spaces

People go to local public spaces to get outside, exercise, and meet the neighbors. With more people working from home, high-quality open spaces within walking distance will become more valuable. Neighborhood parks — already essential — can host community gatherings and events. Elmwood’s Willard Park, filled with sunbathers and picnics on any sunny day, also offers movie nights and Easter egg hunts. We could build on the slow streets programs implemented near Elmwood and elsewhere during the pandemic to make low-traffic streets a permanent part of each neighborhood.

Black Lives Matter speaks to longstanding exclusion and discrimination in our public open spaces. Parks and public spaces that connect people and welcome diversity and inclusion can impart a sense of belonging and community trust. Well-designed and maintained parks can reduce the isolation of people and communities, nurture community dialogue, and reconnect the social fabric of neighborhoods frayed by sprawl and redlining. We should design our public spaces so that people of different backgrounds feel they belong.

5. Create “15-minute cities”

The 15-minute city concept gained momentum with Covid-19. A 15-minute city provides access to food and services within walking and biking distances of all homes; offers a variety of housing types and affordability levels; includes green spaces for everyone to use; and gives multiple purposes to buildings. A 15-minute city allows places to better handle health, economic, and climate crises, increasing neighborhood resilience and social interaction.

Walkable Main Streets like College Avenue in Elmwood play an important role in 15-minute cities. These streets provide community amenities for vibrant and active neighborhoods and may see renewed activities and businesses. But for the many residential subdivisions built without commercial uses, walkable retail will be more difficult to achieve — but not impossible. We suggest two options:

Accessory commercial units

By loosening the restrictive zoning that has limited urban activities for the last century, we can create small businesses in our homes. “Accessory Commercial Units” (ACUs) in residential zoning districts can make space for small home-based businesses — bakeries, juice shops, homegrown produce, art studios, neighborhood cafes, and barbershops — visible from the street and engaging to pedestrians. ACUs can diversify and strengthen social life and foster entrepreneurship in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Who knows what might grow from these seeds? H-P got its start in a garage. The pandemic gave rise to small back or front yard offices that are among the most sustainable ways to bring life to neighborhoods — and fight climate change. These small spaces, often around 120 square feet, create a work/life separation that many people need.

Mobile food strategy

Mobile food facilities could be great additions to neighborhoods that lack walkable Main Streets and fixed-location restaurants. As temporary facilities, they offer access to wholesome food without the expense of a take-out or sit-down restaurant. Unlike traditional food trucks, these super trucks provide food trailers, carts, pop-up shops, awnings, and kiosks. Mobile grocery facilities such as Chicago’s Fresh Moves Mobile Market could alleviate food deserts.

Conclusion

While working from home is not an option for essential workers, more of us may be working from home in the future. Neighborhood cafes, restaurants, and co-working facilities will flourish — once the fear of the pandemic subsides — and local amenities like parks will return to high levels of use. The pandemic isn’t going to change everything about the ways that we live and work. But our stressed-out commute world might look more like our homebound life in 2020, and some subdivisions could begin to look like Elmwood. And that could mean we pollute less, waste less time commuting, and know our neighbors and family better.

John David Beutler, AICP, has worked as a mission-driven planner and urban designer connecting urbanism, land use, and transportation for the last 20 years. First at Calthorpe Associates and then Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), he is now an independent consultant. John focuses on the importance of human-scale design in addressing sustainability and equity from the street to the neighborhood, city, and region. You can reach him at johnbeutler@hotmail.com.

John David Beutler, AICP, has worked as a mission-driven planner and urban designer connecting urbanism, land use, and transportation for the last 20 years. First at Calthorpe Associates and then Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), he is now an independent consultant. John focuses on the importance of human-scale design in addressing sustainability and equity from the street to the neighborhood, city, and region. You can reach him at johnbeutler@hotmail.com.

Leila Hakimizadeh, AICP, is a socially aware, passionate, urban planner and designer who applies measures of diversity, equity, inclusion, public health, and sustainability to facilitate community engagement and plan for the future of cities. She has 14 years of experience in land use and transportation planning, urban design, and housing for the public and private sectors in Canada and the US, at the building, neighborhood, city, and regional scales. You can reach her at leila.hakimizadeh@gmail.com.

Leila Hakimizadeh, AICP, is a socially aware, passionate, urban planner and designer who applies measures of diversity, equity, inclusion, public health, and sustainability to facilitate community engagement and plan for the future of cities. She has 14 years of experience in land use and transportation planning, urban design, and housing for the public and private sectors in Canada and the US, at the building, neighborhood, city, and regional scales. You can reach her at leila.hakimizadeh@gmail.com.

[Ed. note: According to KQED News, single-family zoning was first implemented in the United States by the City of Berkeley in 1916 and applied to the Elmwood neighborhood featured in this article. See “The Racist History of Single-Family Home Zoning,” an article that advises planners to recognize the impacts historical zoning decisions have on their communities. Also see Northern News, September 2020, for information on research on single-family zoning cited in the KQED article.]