Editor’s note: This post was originally published on brookings.edu by Adie Tomer, Jennifer S. Vey, and Caroline George on March 10, 2022

Thanks to historic commitments by Congress and resilient local economies, the next five years have the potential to be a grand era of reinvestment in metropolitan America. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) have committed billions of dollars for communities to modernize their infrastructure networks, ranging from older water systems to cutting-edge broadband. Meanwhile, the House and Senate are set to make big bets on innovation-focused growth centers and targeted industries. State and local budgets also performed better than expected through 2020 and 2021, leaving additional fiscal resources available for economic and community development.

Periods of intense investment like this don’t come around often. Communities and the country need projects and policies that deliver transformative, long-term value. That’s where planning comes into the picture.

Most metro areas already have established economic and workforce strategies, transportation plans, and comprehensive housing and land use plans to prioritize what industries to invest in, where to develop real estate, and what infrastructure is needed to connect them. But if metro areas can coordinate those long-range plans around common goals, the chances of delivering lasting value go up. If not, expensive projects could fail to maximize outcomes — or worse, end up working against one another. Either way, a generational opportunity would be wasted.

Unfortunately, there are few existing mechanisms or incentives to encourage this sort of coordination. Even though the federal government formally promotes regional economic strategy-building, there is no requirement that different plans talk to each other. Coordination also isn’t required between state and metropolitan plans, or between plans developed by neighboring jurisdictions within the same metro area. The situation gets considerably more complicated in the country’s largest metro areas, which are home to the most jurisdictions, the most diverse industries, and the widest array of investment alternatives.

The federal government helped start this next great wave of metropolitan capital investment, so it should ensure that investment will be used to best effect. We recommend Congress establish a new planning coordination program within the Economic Development Administration (EDA), which would support local governments and business organizations in metropolitan areas of at least 1 million people to formally integrate objectives and priority projects across multiple long-range plans. For a relative pittance compared to the costs of capital projects, the federal government can incentivize metropolitan partners to develop the coordination template America needs to make good on its investment ambitions.

The bones of America’s planning paradigm are strong. Cities, counties, and special-purpose governments like utilities use tools such as zoning codes and capital budgets to decide where public dollars are spent and attempt to influence where private investments occur. Metropolitan planning organizations and councils of government convene local governments to plan regional investments, particularly interjurisdictional transportation like highways and transit lines. The private and civic sectors play a role too, often working with local governments to design long-range economic development strategies, including how to deliver more inclusive career pathways, what big bets to make on innovative industries, or drafting master plans for specific districts.

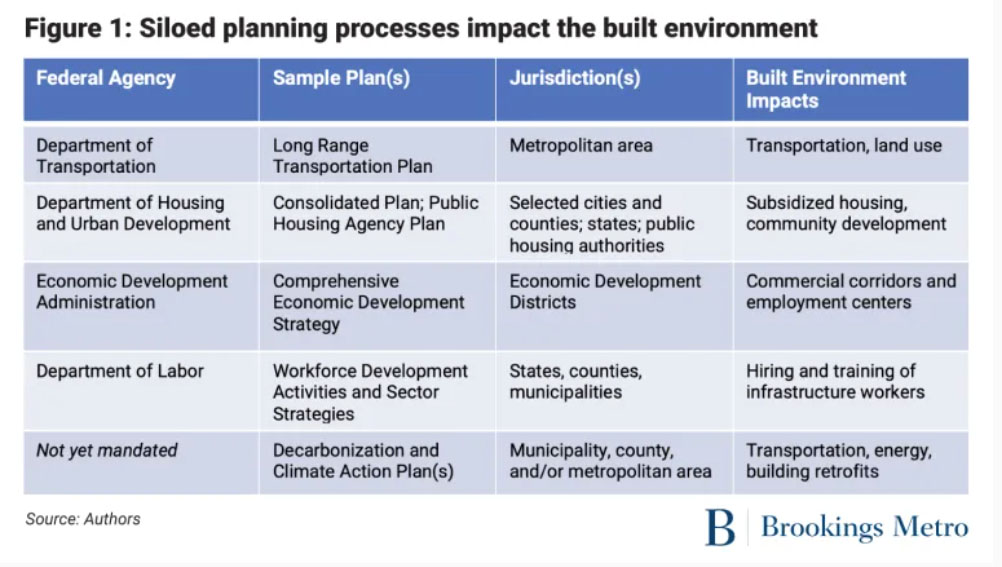

The federal government is also an established partner in many planning exercises. Since 1991, federal surface transportation law mandates that metro areas designate a regional government to lead transportation planning and, at least every five years, develop a long-range transportation plan. Laws administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) mandate the creation of three- to five-year consolidated plans to qualify for agency grants. The Department of Commerce and the EDA use the certification of a Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) or equivalent plan every five years to qualify for a range of EDA grants. The Department of Labor funds workforce development boards to define and act on regional workforce priorities. And these are just a sampling of federal planning requirements.

Yet for all the planning taking place, there is often little coordination among these various processes, and the result is formal plans that often directly contradict one another. In some cases, those contradictions may occur between the local and regional levels. This is the case when a regional entity like the Association of Bay Area Governments in metropolitan San Francisco wants to build more housing, but locality after locality limits housing construction. In other instances, the conflict may be within different planning documents written by the same local government or regional entity; for example, most large American cities have been unable to match their land use and development practices to their climate goals. Even timing can be a conflict: A metro area’s major planning cycles can fall on different years, with different offices and staff leading them, making coordination all the more difficult.

Yet for all the planning taking place, there is often little coordination among these various processes, and the result is formal plans that often directly contradict one another. In some cases, those contradictions may occur between the local and regional levels. This is the case when a regional entity like the Association of Bay Area Governments in metropolitan San Francisco wants to build more housing, but locality after locality limits housing construction. In other instances, the conflict may be within different planning documents written by the same local government or regional entity; for example, most large American cities have been unable to match their land use and development practices to their climate goals. Even timing can be a conflict: A metro area’s major planning cycles can fall on different years, with different offices and staff leading them, making coordination all the more difficult.

This is a missed opportunity. With so much complementarity between infrastructure, real estate, and economic and workforce development, making sure formal plans talk to one another can increase the odds that metropolitan development leads to agreed-upon outcomes—advancing particular industry sectors, for example, or enhancing local commercial corridors. That means ensuring that policies and strategies identified in these plans—focused on businesses, transit, land use, education, marketing, parks and public space, etc.—are aligned toward these specific ends.

Now is an ideal time to support this kind of coordination with federal incentives. The federal government knows this is a good idea — it’s why HUD, the EDA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Transportation all run offices and programs to promote the concept. Even the Government Accountability Office has affirmed the need, particularly within economic development. The federal government also has the regulatory power to compel regional and local actors to work together across different disciplines. What regions require are the resources and staff time to help them do it — and the mandate to make it multiple people’s job. Now, with EDA reauthorization conversations starting in Congress, there is a legislative vehicle to address the need.

The new EDA planning coordination program we propose would provide grants to support staffing resources within those entities responsible for regional planning. Since CEDS already includes industrial and infrastructure goals, CEDS authors within a given metro area could be the primary recipient(s) and make sub-awards to transportation, housing, workforce, and other regional planning entities. The grants would cover staff time to regularly convene regional actors, coordinate with the public (including a steering committee), and revise formal plans. The core output of the program would be evidence of those revisions, including adjustments to overarching goals, capital projects, and other policies.

Ideally, Congress would help the EDA improve its staffing to support these new regional activities. Staff in the EDA’s regional offices are vital conduits for explaining how federal programs work, sharing best and failed practices from across the country, and communicating needs back to EDA headquarters. Likewise, the EDA’s Washington, D.C. office should receive more staffing to consolidate all the lessons and experiences into a common knowledge hub for nonparticipating regions, smaller places, or peers across the economic development and research communities.

Some metropolitan leaders are already experimenting with new ways to merge regional planning and major investments. In Kansas City, the bistate KC Rising initiative between Missouri and Kansas brings together the business, government, and civic communities to align their efforts around seven common pillars. And the multisectoral board of the Greater Portland Economic Development District in the Pacific Northwest used their CEDS process to formally adopt a new set of integrated values and principles. These are the kinds of emerging models that a new EDA program can support — and that the EDA should seek, collect, and share with other regions to inform their planning work.

Congress should finish the job it started when it approved historic levels of investment in metropolitan America by supporting a coordination program like the one recommended here. Planning is far cheaper than capital projects or tax incentives — and it is money well spent if it ensures physical investments lead to better projects with better outcomes that advance regional prosperity, resiliency, and opportunity.

Adie Tomer is a Senior Fellow at Brookings Metro. Jennifer S. Vey is a Senior Fellow at Brookings Metro and Director of the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking. Caroline George is a Senior Research Assistant at Brookings Metro.