By Jillian Zeiger, AICP, and Stefan Pellegrini, AICP, March 10, 2023

In 2017, fifteen bills were signed into law to address California’s estimated housing shortage of 3.5 million units. A key policy feature of these bills, including SB (Senate Bill) 35 and the Housing Accountability Act, was streamlining the entitlement process for affordable housing development by replacing public review and subjective guidelines with Objective Design and Development Standards (ODDS). Like many California communities, Marin County was infamous for lengthy approval processes that often resulted in multi-year housing development efforts. At that time, most jurisdictions in the County had few ODDS to apply and streamlined approvals for housing projects were rare. ODDS became an important tool for Bay Area jurisdictions to address State law requirements and facilitate ministerial approvals for housing projects. In Marin, multijurisdictional collaboration was key to meeting this need and provided a model for regional implementation to effectively address the State’s housing crisis.

In December 2018, Marin County Community Development Agency staff established the Housing Working Group (HWG), a collaborative composed of planning directors and senior staff from jurisdictions throughout the County, to facilitate discussion about and coordination on housing issues. What started as a place to discuss and interpret State legislation soon transformed into a Countywide housing policy working group. In January 2019, HWG members discussed ways to use funding from SB 2 (Building Homes and Jobs Act) Planning Grants to partner and collaborate. Ten cities eligible to receive only a small grant award agreed to pursue three projects together; one of these became the Marin County Objective Design and Development Standards Toolkit project. Without this collaboration and with limited individual capacity, jurisdictions would have struggled to stretch the grant funding to complete ODDS amid other housing-related needs.

Working group members initially responded to the idea with skepticism, as jurisdictions claimed substantially different situations and struggled to recognize enough similarities to justify collaborating. HWG leadership (led by Marin County’s Jillian Zeiger, AICP) and a consultant team led by Opticos Design (Stefan Pellegrini, AICP, and Tony Perez) came together to craft a strategy that would address the needs of the working group members: Jurisdictions would be provided with a base ODDS “toolkit,” leaving sufficient funding for each to customize it. Customization meant selecting local context-appropriate standards and might involve modifying individual standards, conducting site testing to apply the toolkit to housing sites, or preparing technical studies to determine additional content.

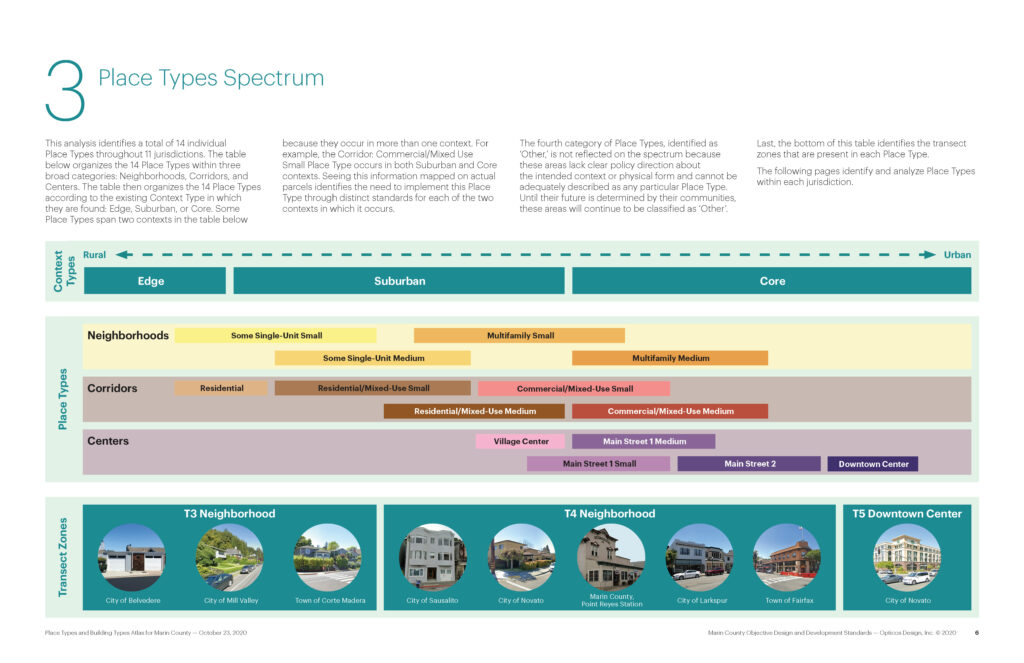

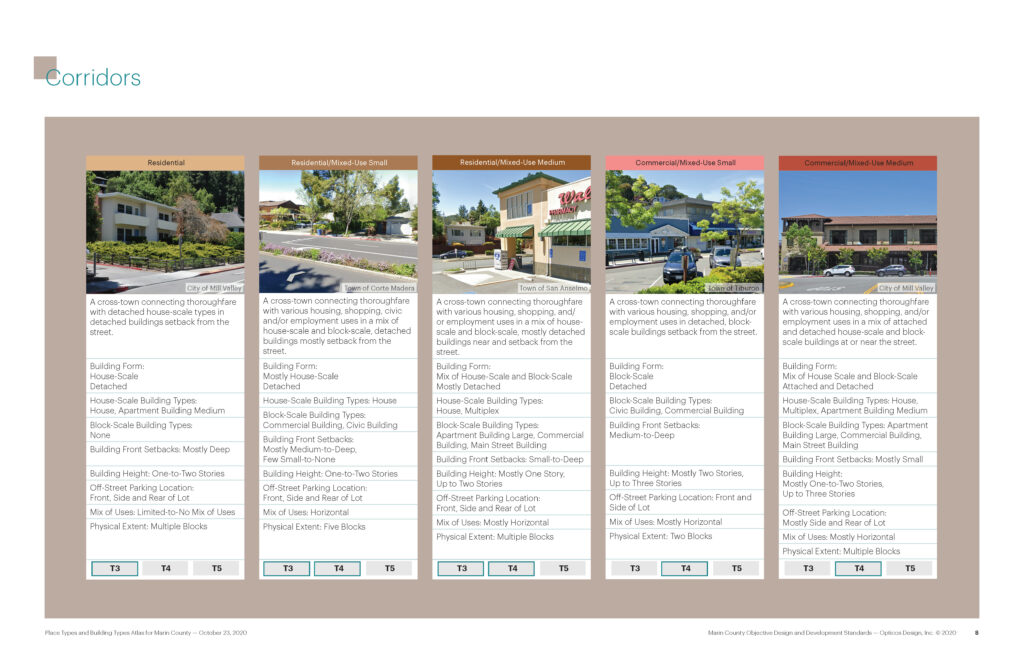

The team focused its early work on proving that a common toolkit made sense by demonstrating the jurisdictions’ shared needs. An existing conditions report that analyzed nearly 800 parcels contributed by participants and a “Place and Building Types Atlas” that classified the range of places where each was seeking to accommodate housing indicated that the communities shared many similarities. These included the size and intensity of their downtowns and corridors and issues and needs on their vacant sites that could be addressed with a common set of standards. The team’s early deliverables helped establish the final toolkit’s organizing framework and ensure its broad applicability. HWG members identified solutions and shared the results of their parallel individual efforts, including site testing activities that explored potential outcomes of applying objective standards to housing opportunity sites, development pro forma analyses suggesting project feasibility, and architectural documentation that cataloged locally recognized stylistic vernacular characteristics.

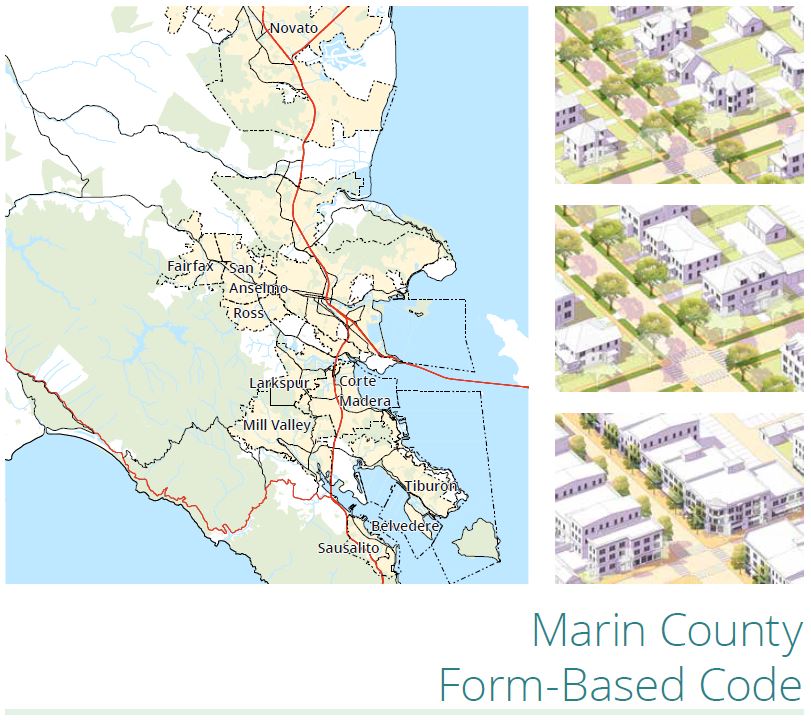

The resulting Marin County Objective Design Standards Toolkit (Toolkit) is organized as a Form-Based Code. It supplies a series of zone districts that regulate appropriate housing types and densities for the range of places found in Marin, from multifamily neighborhoods to neighborhood-scaled centers, mixed-use corridors, and small-town downtowns. Supporting standards address other anticipated community needs, including building types, frontages, parking, and civic spaces, as well as guidance for six common architectural styles.

Getting to objective design standards means “objectifying” things that have historically been used and applied as design guidelines. In Marin, for example, the architectural standards provide basic elements that – when used together – make up a style, such as eave details, window sizes and proportions, wall materials, and external elements like balconies. Objective standards address only essential dimensional requirements in order to promote architectural creativity.

The Toolkit’s form-based approach provides clear outcomes regarding housing yield and form, and its place-based approach provides a simple and direct way to communicate what kinds of places can emerge from rezonings in the absence of conventional and time-consuming visioning processes. Several jurisdictions, including the unincorporated County, needed to draft and adopt objective standards simultaneously with updates to their Housing Element. As they grappled with accommodating increased Regional Housing Needs (RHNA) allocations, the Toolkit was used in new geographies where rezonings would be required. This helped ensure a place-based approach to growth.

The Toolkit is pre-assembled in a way that eliminates the need for planners to do “brain surgery” on existing zoning codes. While a community could elect to adopt the Toolkit in its entirety, none is expected to do so. The Toolkit supports designing jurisdictional-specific approaches because zone districts can be selected to match desired place types, intensities, and the supplemental standards that most closely match how much they want to regulate. Most jurisdictions are deciding to customize and adopt the Toolkit as “overlay” zoning, which enables them to apply objective design and development standards only in cases where they are needed by State law.

Jurisdictions in Marin County are at various stages of customization and adoption of the Toolkit. Five cities (Belvedere, Corte Madera, Marin County, Sausalito, and San Anselmo) have either adopted – or will soon adopt – a customized version, and three more are in the pipeline. Corte Madera was one of the first cities to refine and adopt the Toolkit. The City engaged the public early on in the process, and a stakeholder committee that included designers and commissioners championed the Toolkit when it was presented to the Corte Madera City Council.

In Marin, shared needs and limited resources resulted in an innovative response to regulatory requirements. Multi-jurisdictional participation in a collaborative design and development process resulted in an adaptable and transferable toolkit that would ensure new housing development responds to existing context and reflects a sense of place. In the meantime, State policies have continued to evolve and expand the need for objective standards while many planning agencies continue to have limited resources and capacity. For example, 6th Cycle Housing Element requirements and new State laws (such as AB 2011) have spurred a need to rezone larger geographies for housing and, in many cases, revisit the initial scope and extent of ODDS in individual communities.

Current efforts to scale up the Toolkit will further test if this collaborative approach has created an enduring and replicable model for establishing ODDS. In January of this year, ABAG/MTC and Opticos embarked on a 12-month process to expand the Toolkit to a regional model, making it available and applicable to the nine Bay Area counties and their 107 cities and towns. The hope is that it could help to address Plan Bay Area’s goal to construct 441,000 units by 2031.

About the Authors

Stefan Pellegrini, AICP, is a Principal at Opticos Design in Berkeley.