By Arielle Milkman, via Next City, April 28, 2021

City planners ask the public to participate in planning processes, but people are tired of showing up. Here are some of the reasons why.

My friend Tom lives in North Denver’s Elyria neighborhood, down the street from the I-70 highway and within smell of the city’s famously odiferous dog food factory. He keeps a scrapbook that most people wouldn’t. It contains all of the flyers, explainers, invitations to contribute to health studies, meeting requests, and info sessions that have been delivered to his door over the past four years.

Tom, who is an artist, plans to make it into a collage — a reminder, or maybe even a historical record — of the days when planners and researchers knocked on his door all day long — and tried to transform North Denver from a superfund site to a sustainability hub.

I live in Denver too, some 25 blocks south of Tom, also within the smell of the dog food factory. I have spent a lot of time over the past few years trying to understand the city’s growing inequality. By some metrics, Denver leads the U.S. in displacement of Latino residents, and there are meetings — so many meetings — all focused on gathering resident input on coming changes.

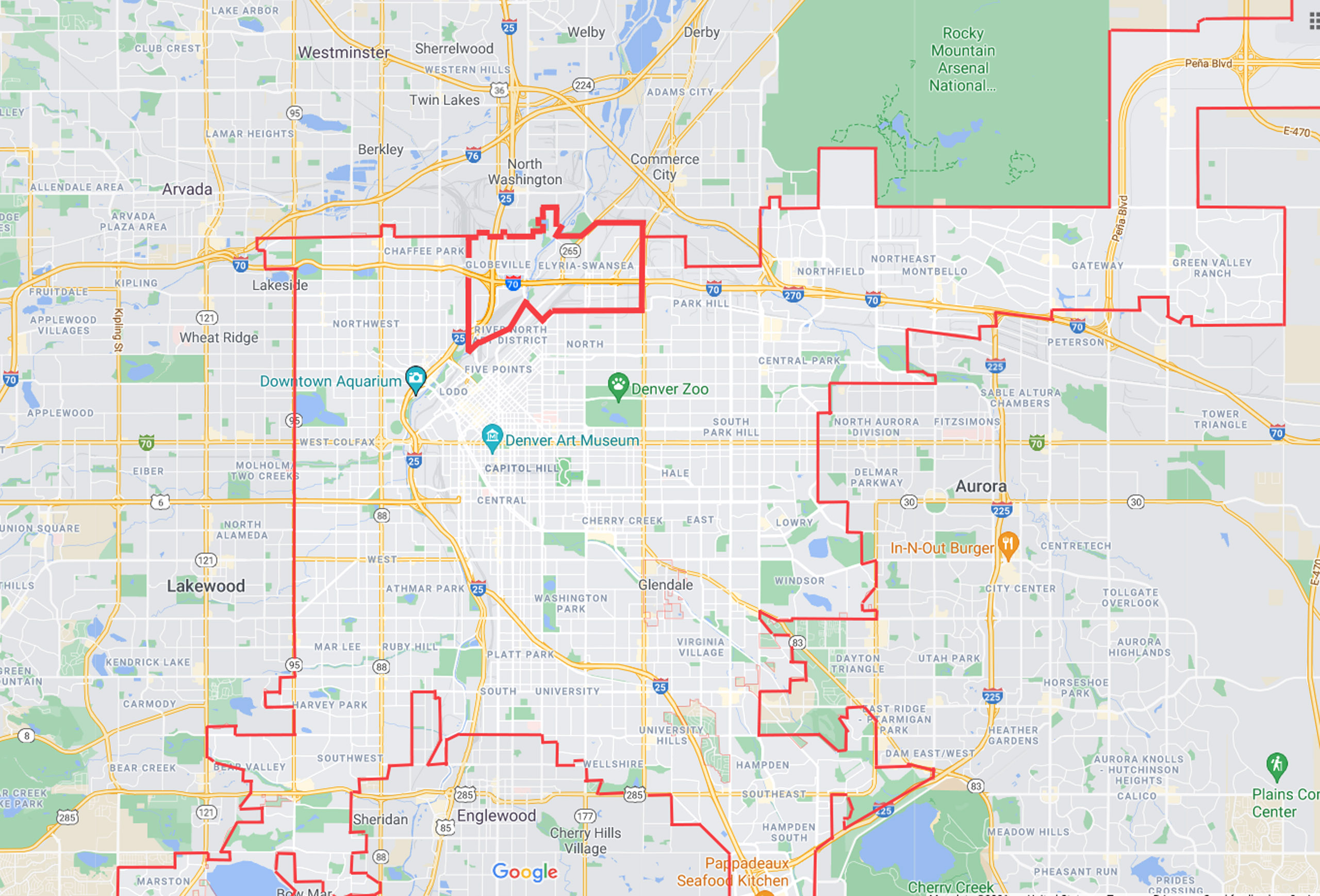

These meetings have a name. Urbanists call them participatory planning. A movement now integrated as orthodox in urban planning schools, participatory planning seeks to involve a multiplicity of voices in urban development projects. In Denver, some of these aim to transform formerly industrial areas like the Globeville, Elyria, and Swansea neighborhoods (locals call this area GES), once the site of heavy metal smelters during Colorado’s mining boom times, from superfund sites to leaders in environmental remediation.

But neighbors living in industrial areas are fatigued. They frequently say that the city seeks their input on projects but doesn’t listen to their concerns. Community engagement specialists in North Denver, on the other hand, are frustrated by low turnout at city-organized meetings. Why does participatory planning — an approach originally conceived to make cities more just — fail?

In Denver, activists say planners failed to account for historic harm in a highway corridor.

Candi CdeBaca grew up in Swansea and was a student at Denver’s Manual High School when the public participation process to redevelop and widen the I-70 highway through GES began in 2003. Sixteen years later, she was elected to city council on an anti-gentrification campaign that included fighting the highway expansion.

“That’s kind of what catalyzed my race for office,” CdeBaca said, referring to the participation system.

“Having participated in several of the I-70 meetings … and a range of other things, I got to see firsthand how community input really just meant show up, complain, and we’re going to do the opposite of what you’re asking,” she said.

In the lengthy process to break ground on I-70, the Colorado Department of Transportation had proposed a redesigned highway corridor that would fix and expand aging infrastructure.

Neighbors instead wanted planners to consider past and perceived future harm — the health impacts of smelters that operated starting in the 19th century, the cumulative effects of air pollution, and a future where, without significant investment in affordable housing, displacement seemed assured.

Several lawsuits later, the highway project broke ground in 2018, with some small concessions for affordable housing and pollution mitigation efforts.

Development is continuing at a rapid pace in North Denver, and this time, community engagement practitioners and organizers are trying to learn from past mistakes — by moving slowly and acknowledging the history of the neighborhoods.

Celia Herrera first stepped into Swansea recreation center in January 2020 to gather resident input about the redevelopment of the National Western Center, a historic cowboy venue that will soon host a university campus, shopping, and potentially housing. It presages a future that’s less about celebrating agriculture and more about retail, education, and real estate.

Herrera, who works for the city, knew that something was off about the room. People were exhausted and really hesitant to show up for another meeting. After talking to a resident who was candid with her, Herrera said she learned that the city had been contracting out engagement work to public information firms that cycled in and out of the community with a speed that bewildered neighbors.

She realized she needed to slow down to build relationships with residents, bringing as many people as possible into the fold while acknowledging the long-term contributions of the three or four people who always show up.

Her experiences growing up between Denver’s nearby Park Hill and the East Side during the 1990s as a person of color help her contextualize where neighbors are coming from. She understood that people have a historically informed relationship of distrust with the city, developers, and other institutions. “I didn’t set out to find a ‘job’ as a community engagement consultant,” she said. “Community has just always been at the foundation of my work.”

Ren-Caspar Smith is a Sierra Club organizer working in North Denver and nearby Commerce City around energy transition for the Cherokee Generating Station, a power plant that provides energy for the area using natural gas.

Smith also pointed out that North Denver community members’ distrust of the city and the environmental movement extends back far beyond the starting and ending point of community input-gathering phases. Big green organizations such as the Sierra Club historically focused on protecting wilderness instead of people in cities, and an early 2000s alignment with anti-immigrant politics has been destructive for coalition-building with Latinx communities.

Instead of pushing participation in big initiatives, Smith focuses on supporting ongoing efforts, like an Earth Day celebration neighbors put together this year in GES. “I need to learn more and shut my mouth and slow down,” Smith said.

“Every time I think I’ve done that, I then have another moment where I’m like, wow, I need to slow down more.”

Research shows that participatory planning addresses the needs of older, whiter, and wealthier residents.

At community gatherings in the North Denver neighborhoods of Globeville, Elyria, and Swansea, neighbors frequently say that they have to sacrifice time with family, work, or both in order to show up to participatory planning meetings. It’s harder for people with kids, long work hours, or lower incomes to contribute, so recently some community activists who participate regularly have advocated to be paid for their time, pointing out that community engagement professionals are salaried.

Recent research by Katherine Levine Einstein, a professor of political science at Boston University, sheds light on how race and class can show up in some participatory approaches to new housing. In a study of participation in zoning forums for new housing development in Massachusetts, Einstein found that participants who gave their feedback to city councils opposing new affordable housing developments were whiter, older, and wealthier than the average resident in their cities.

In a different study investigating the discourse of community engagement processes around the National Western Triangle development in Denver, education researcher Sabrina Sideris found that residents “participated without power.” In other words, community members showed up to meetings guiding development but their feedback was not incorporated in planning decisions.

Cities like Denver do lots of community engagement. But there’s no standardized way to make sense of the data.

Over the course of 15 years, the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) conducted 432 community meetings about the Central 70 highway development, before deciding to put the freeway underground in key sections of the city. Neighborhood activists instead wanted the department to investigate an alternative route for the highway through less dense, more industrial Commerce City.

“There’s nothing that holds anyone accountable for … taking in feedback,” said Nola Miguel, the executive director of the GES Coalition, a group that has organized around housing access since 2015. “It really frustrates me that equity and community process are put in the same sort of box when an equitable process is very different from a general community process.”

If the engagement process was good enough for the city but not rigorous enough for activists, it raises the question: What counts as good participation? Surveys, meetings, flyers, coffee hours, focus groups, and petitions can all help planners understand community needs. But without a more comprehensive approach that includes standards for participatory approaches, cities may continue to reach their targets for involving constituents in the planning process while the most vulnerable residents go unheard.

A way forward.

There isn’t a quick fix in the cards for Denver, but there are some bright spots on the horizon. CdeBaca said that the impacts of Covid-19 social distancing measures forced city meetings to go online in a form that’s now recorded and more accessible and transparent. She wants to see heavily impacted communities use a Community Bill of Rights, a strategy promoted by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund to increase local control in decision-making. And a more holistic approach to engagement in the planning process — rather than one that’s project based — could decrease planning fatigue overall.

North Denver is also now home to a Community Land Trust developed by the GES Coalition. Community land trusts, a model where land is owned communally and individuals or families own the house they live in, are increasingly popular tools to prevent displacement and build housing stability in U.S. cities like Denver.

“Having that stability for the long-term … can focus your time on your work, your education, your community … all those things that a lot of times, when you don’t have stability, you just can’t add to in life,” Miguel said.

The land trust will make decisions by involving a board composed equally of people who live on the land, GES residents at large, and housing experts.

The key to better participation, for Miguel, is to distinguish community engagement processes at large from equity-focused development. She pointed to tools that other cities have used to judge fairness in development processes — like Minneapolis’ Equitable Development Scorecard.

And in 2020, Denver allocated $1.7 million for participatory budgeting, a process in which residents decide how to spend a portion of the city’s budget. My colleague Vincent Russell, who studies participatory budgeting at the University of Colorado, found that in the process participants form new alliances and learn how to navigate bureaucracy with community members they wouldn’t otherwise encounter. Denver’s current investment in participatory budgeting is small, though — the equivalent of just $2.37 per person.

Participation will be a key component of U.S. cities’ efforts to design climate resilience processes in neighborhoods heavily impacted by industry and real estate speculation. That’s why CdeBaca wants her constituents to keep showing up. “While it is annoying and frustrating to participate in rigged processes, I think it’s critical that we are participating, one, so we can understand the deficiencies, and two, so that we can map out a path to doing something better.”

Arielle Milkman is a researcher and writer based in Denver, Colorado. She is a graduate student in cultural anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where she is focusing on the politics of environmental remediation.

Arielle Milkman is a researcher and writer based in Denver, Colorado. She is a graduate student in cultural anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where she is focusing on the politics of environmental remediation.

A version of this article appeared in Next City. Republished with permission.