By David Driskell with Ian Carlton, Tyler Bump, and Michelle Anderson, August 11, 2021

You can’t always get what you want.

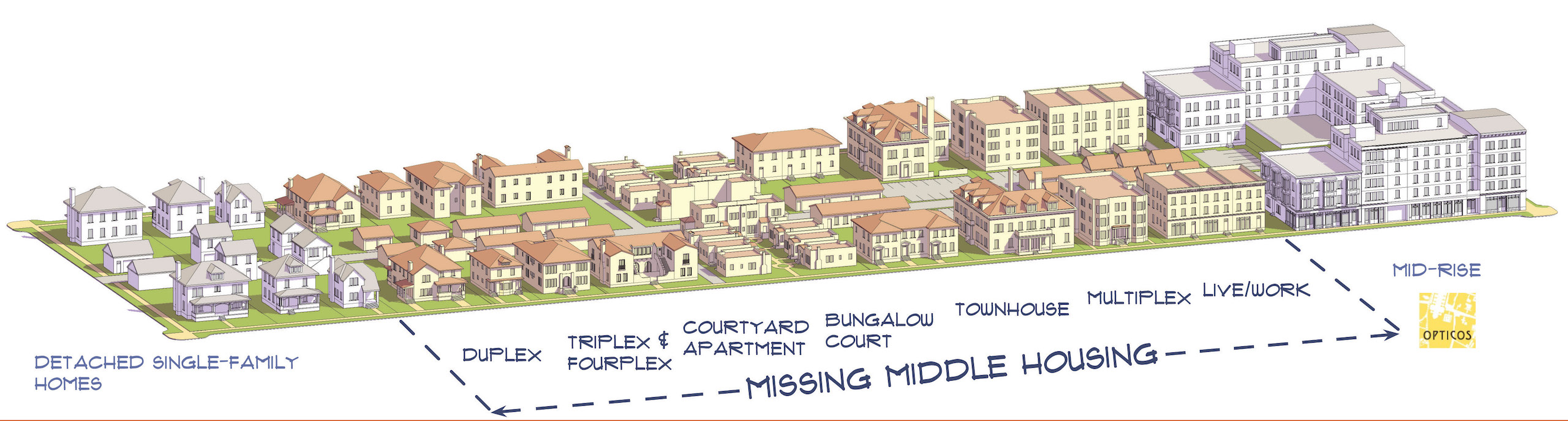

Over several decades, detached, for-sale, single-family homes, and larger rental apartment buildings have dominated new construction. This has been driven by a combination of land use regulations, lending practices, construction litigation risk, and market forces — leaving duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, and small apartment or condo buildings largely out of the mix. In response, many communities and the State of California are looking at ways to reintroduce neighborhood-scaled “missing middle” housing in existing single-family neighborhoods, driven by the desire to provide more diverse and more affordable living opportunities, including more affordable for-sale housing.

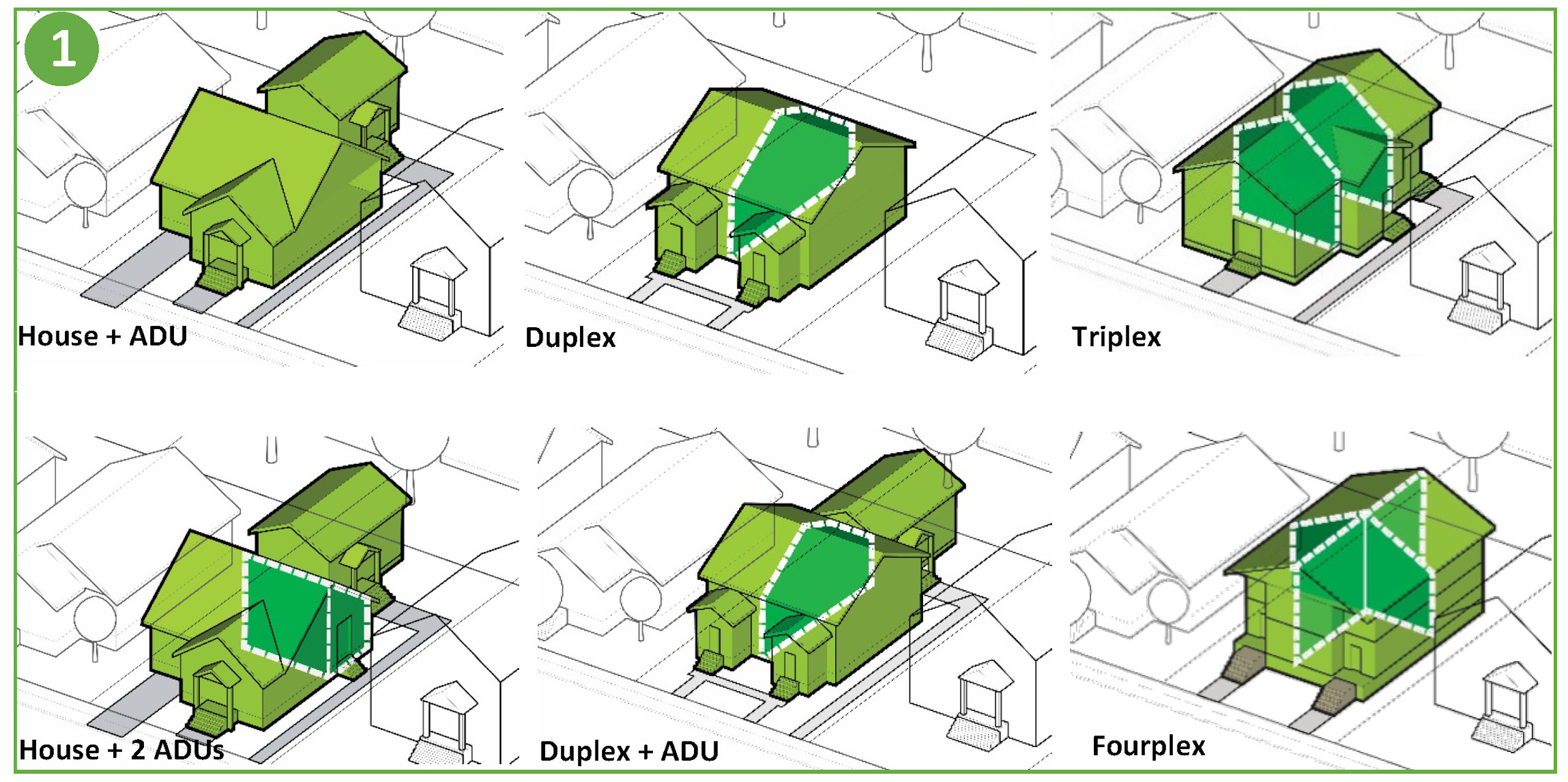

At the state level, Senate Bill 9 is currently the highest-profile effort to open up single-family neighborhoods to more diverse housing. Similar to the state’s recent ADU legislation, it would create a way to subdivide lots and to build duplexes, either through conversion of existing homes or new construction. It would, in effect, replace single-family zoning with duplex zoning in much of the state. Not surprisingly, SB9 is getting a lot of attention and opposition.

Driven by desires for greater affordability, choice, inclusion, and equity, plus a strong need for more housing overall, Sacramento, San Jose, San Diego, Berkeley, and other cities in and beyond California are contemplating a wide range of changes to single-family zoning to drive different outcomes, including middle housing.

Proposing changes to single-family zoning is not for the faint of heart. Few neighborhoods embrace change. Current residents like where they live and don’t see why they should sacrifice and change to accommodate newcomers. That attitude may be shifting as more homeowners experience the impact of the housing shortage (as they look to downsize, or their kids look to move), but rezoning single-family neighborhoods remains the third rail of land use planning.

We have been working with jurisdictions to help them understand whether taking this bold step will help achieve their goals. The results are not always what you might expect.

If you zone it, will they come?

It takes more than a zoning revision to facilitate change on the ground. Property owners, investors, builders, and buyers have to align around the opportunity and be willing to make the effort, and all will need to see a higher economic return before shifting from ‘what is’ to ‘what could be.’ There are zone districts in every community that neither produced the development envisioned nor fulfilled their potential until conditions changed and development interests responded.

Over the past months, we analyzed potential “middle housing” rezonings for several Bay Area and Central Coast communities. While we cannot share the specifics of the analyses, we can share our insights:

The results were similar in each case. Even with the opportunity to create two or more units on a property, single-family homes are often the most economically feasible option, whether by retaining an existing home or building a new one.

While many variables (such as local housing prices and demand, land and development costs, and jurisdiction-specific development standards and processes) determine the potential, we found that the overall impact of switching from “single-family” to “duplex/triplex/townhome” does not have the outcome some hope for and others fear.

In one analysis completed for a strong market jurisdiction considering expanding existing medium-density zoning to adjacent areas, we found the expansion would be unlikely to create market-feasible opportunities for middle housing types in the rezoned areas. In fact, in a process that is already underway, older duplex and triplex units are being purchased and converted to luxury single-family homes, and the jurisdiction will likely see a continued loss of existing middle housing in current medium-density zones.

A similar conclusion was reached when the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley worked with Mapcraft Labs to complete a statewide analysis of the potential impact of SB9. Their study found that the proposed SB9 legislation would enable newly feasible development (i.e., add financial feasibility where it was previously infeasible) on just 1.5 percent of parcels with existing single-family homes statewide. And only a portion of those physically and financially feasible development opportunities would actually be realized because they are largely dependent on individual property-owner decisions. While some regions and jurisdictions would see more opportunities (and some would see fewer), there is no evidence that the legislation would lead to wholesale change in single-family neighborhoods. On the contrary, the analysis suggests that many neighborhoods would see no change at all.

But why would that be?

The reasons vary. Housing submarkets differ widely, as do the specifics of any parcel or neighborhood and the local regulations that enable or inhibit development. That said, there are several important, high-level dynamics behind the not-really-that-surprising results.

First, there are a lot of wealthy households in California generally and the Bay Area specifically, and they like living in single-family homes. Combine that with a finite supply of single-family homes in highly desirable neighborhoods close to jobs, services, and amenities, and you have the price escalation we have seen in the past decade as well as the analysis results described above. People who can will pay a premium for a single-family home. Duplexes, triplexes, and townhomes may not be cheap, but they are generally smaller and offer less privacy. And they may not be as easy to finance, so they do not bring the top dollar commanded by a larger single-family home. In many communities, the strongest housing trend is in replacing older “modest” single-family homes with larger, high-end single-family homes. Even with a change in the underlying zoning to allow more units, that trend is unlikely to change soon.

Second, even luxury single-family rentals can produce enough income to out-compete other housing types and justify second home purchases by households with the means. This varies widely across jurisdictions and locations, but in many communities, high-end single-family rentals are hot. Even where short-term rentals (less than 30 days) are not allowed, the monthly rental income for a high-end single-family home ($8k and up) can outperform the economics of either for-sale or rental duplexes. In communities where short-term rentals are allowed, luxury single-family home rentals are often the hands-down winner.

Third, and on the supply side of the equation, the complexities and realities of development standards, fees, and processes can undermine the physical and economic feasibility of multi-unit developments despite the best intentions. Depending on the lot size and configuration, the combination of parking standards, setback requirements, height limits, FAR, minimum lot size requirements, and/or lot coverage limits can make a multi-unit development economically infeasible. Fees can be structured to advantage multi-unit developments, but scale benefits are rare. While some SB9 provisions and local code changes can reduce or eliminate some of these challenges, the complexities of implementation can be a significant deterrent to multi-unit development compared to a single-family home.

What’s a planner to do?

While planners can’t control the market, they can help ensure that market realities and development economics are front-and-center when crafting (or even just considering) zoning and development standards to achieve community-desired outcomes. (If you’re going to touch the third rail, be sure it’s for a good reason!)

Every jurisdiction has specific context issues that will shape the housing solution that works best for them; but if you want to give middle housing development an edge in the marketplace, consider these actions:

- Link structure size limits to the number of units to be created. If the structure is for a single-family home, it should have a smaller maximum size than if it is going to be for two or more units. This can help respond to the issue of older homes being bulldozed and replaced with large new single-family homes, creating more bulk but not more housing. At a minimum, scale and building size limits for middle housing should not be more restrictive than for new single-family detached homes.

- In medium-density zones, make single-family a conditional or prohibited use. While existing single-family homes would remain, this change can head off the loss of older multi-unit housing to single-family development while also encouraging middle housing when properties transfer and redevelop.

- Stop controlling density through units-per-acre. Many people think that controlling “dwelling units per acre” (DUA) will result in attractive low-density or mixed-density neighborhoods. But a low DUA can result in plenty of bulky, oversized single-family homes. Raise the DUA and expand the allowable range so that middle housing types are achievable — and/or shift to form-based standards to control building bulk while allowing multiple units within the building envelope. (And don’t require larger minimum lot sizes for multi-unit developments.)

The City of Portland’s Residential Infill Project created new rules to allow more housing types in many residential zones and allow larger building envelopes for structures with more units. Credit: City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability - Focus middle housing in areas where it’s most desired. There’s a growing part of the market that is happy to choose smaller housing units in locations that are walkable and rich with amenities, close to neighborhood commercial districts and to great transit. These areas are where middle housing is likely to perform well compared to residential areas where car travel dominates.

- Revise parking standards to facilitate multi-unit development. If your zoning says a triplex is allowed, but your parking standards require 1.5 or 2 spaces per unit, it’s unlikely that a triplex is feasible on most residential parcels. That’s true physically in terms of the space required, and true economically based on the cost of structured parking. As a starting point, consider reducing or even eliminating parking requirements for middle housing within walking distance of major transit and services. Another approach is to establish off-site parking policy and let the market determine on-site parking.

- Ease the process for middle housing. Permitting time and costs can affect all types of development, but it shouldn’t be more onerous to gain approval for middle housing than for a single-family home. That’s especially important while the market is first responding to new middle housing opportunities. Minimize discretionary review for middle housing and avoid conditional use restrictions for middle housing in lower density zones.

The bottom line

Successful middle housing outcomes are possible, but they won’t happen just because we add them to the list of allowed uses. As in most rezoning, change will be incremental. Take the long view. Pay careful attention to the market dynamics that drive development decision-making as you craft land-use policies that — over time — can create more integrated, more affordable neighborhoods, with a diversity of housing.

To craft middle-housing zoning for your jurisdiction, use the many great resources out there, and learn from your peer cities.

- One of the more comprehensive policy projects, adopted in Portland, OR, in 2020, has online resources worth visiting — and a recent article in Sightline tells the story of how the policy went from idea to reality (avoiding eight brushes with death along the way).

- A great website launched in 2016 by Opticos Design, Missing Middle Housing, and a book of the same title by Daniel Parolek, provide a great introduction to the topic, case studies, and detailed guidance for crafting regulatory frameworks that enable and encourage middle housing outcomes.

- And if you’re a planner in a Bay Area jurisdiction, consider joining the Missing Middle Work Group launching in late August. It is sponsored by ABAG under their REAP-funded Housing Technical Assistance Program, and features experts from both Opticos Design and ECONorthwest.

Author David Driskell (left) is a founding principal at Baird+Driskell Community Planning. He recently returned to the practice after two decades teaching participatory planning at Cornell University; serving as Executive Director of Planning, Housing, and Sustainability for the City of Boulder, CO; and serving as Deputy Director for Planning and Community Development for the City of Seattle. You can reach him at driskell@bdplanning.com.

Co-author Ian Carlton (second from left) is co-founder of Oakland-based MapCraft Inc. and directs ECONorthwest teams in the customization of MapCraft’s web applications for public and private sector clients to aid their policymaking, urban planning, and investment decision making. You can reach him at icarlton@mapcraftlabs.com.

Co-author Tyler Bump (near right) is a Project Director at ECONorthwest with a professional focus on the intersection of land use planning and real estate investment, particularly in advising clients on middle housing implementation. He has worked with the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development to help develop statewide model code and minimum compliance standards for HB2001, Oregon’s landmark statewide middle housing bill, and supported middle housing code implementation for cities across the West Coast. You can reach him at bump@econw.com.

Technical contributor Michelle Anderson (far right) is a Project Manager at ECONorthwest who specializes in real estate, land use, and affordable housing policy. She brings her experience developing affordable and conventional multi-family housing to her work conducting development feasibility analysis for public sector clients to support equitable development outcomes. You can reach her at anderson@econw.com.

Ed. Note: A one-hour Zoom class on The Missing Middle — How to build homes for the Middle Class — will be held September 14 at Noon.