Reviewed by Asher Kohn, AICP, April 13, 2022

“Cities are deeply personal,” write James Rojas and John Kamp in the preface of their recently-published book on community engagement, “Dream Play Build: Hands-On Community Engagement for Enduring Spaces and Places.” This simple declaration, that urban planning is about managing senses and emotions as much as it is concerned with geometry and space, is the foundation of an original and thought-provoking book on improving community engagement methodology. The urban form is not just land uses and circulation patterns, of course, it is “individuals who have to compromise through space,” according to the authors. Why not put at the forefront of community engagement the individuals who will be affected by future development and how they will experience the new spaces?

For many planners, community engagement is a system that feels broken. Few schools train their planning students in how to pursue engagement, and as Rojas and Kamp point out, many planners treat engagement like school: brief lectures about planning concepts followed by seminar-style conversations. For academically-trained planners, this may be the most familiar way to talk about about a plan, a project, or the profession. It has diminishing returns, however, especially now, as equity in engagement takes center stage.

Rojas and Kamp recommend that planners instead engage with their senses.

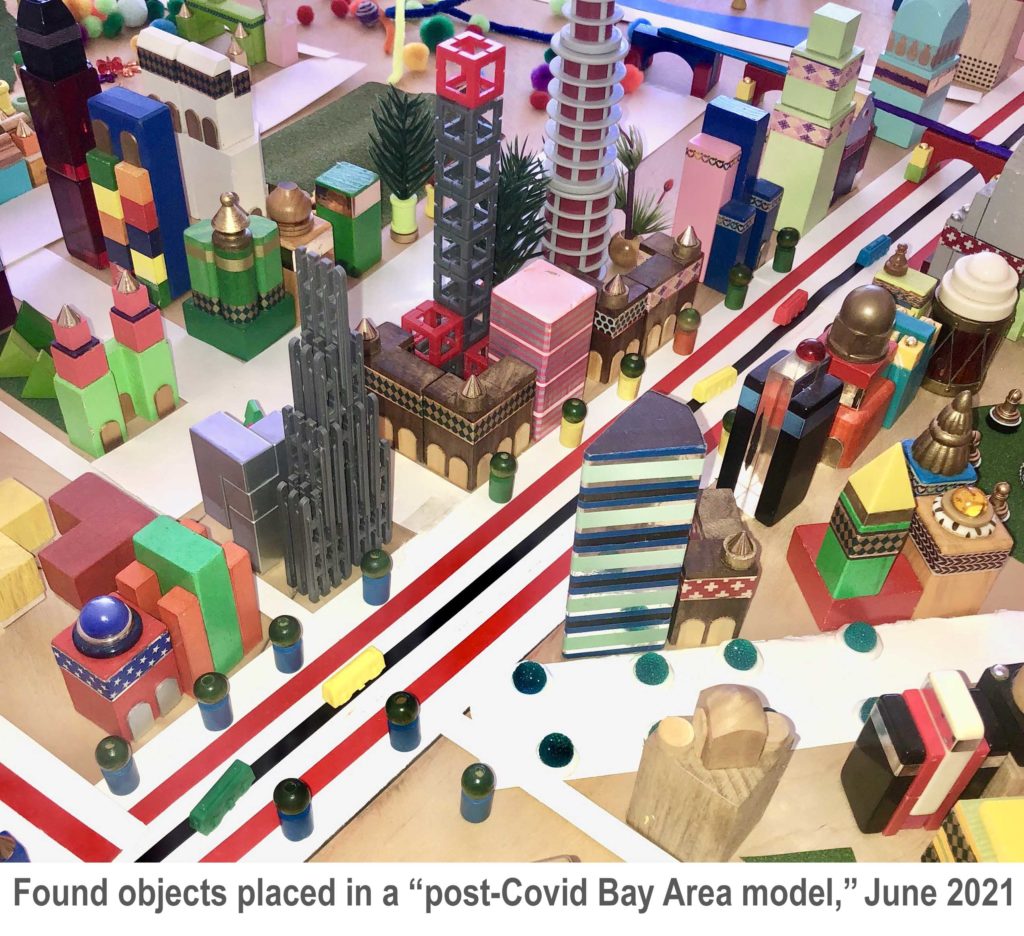

Dream Play Build outlines two engagement programs: model building and site exploration. These programs serve to step back from planning policies and issues and instead allow the community to focus more on emotional reflections. The authors point to “emotions …, moods, and atmospheres” that can be elicited by using abstracted models (hair curlers for buildings and ribbons for bike paths, for example) to represent their neighborhoods, present and future. In their site explorations, the authors ask, “What do you hear? What do you feel? What do you see? What do you smell?” The book gives implementation instructions on how to turn these qualitative feelings into useful planning data, while allowing the community to skip the jargon.

Whereas community engagement may deal with the tools that are needed (to consider infrastructure, for example), the Dream Play Build approach focuses on solutions the community wants to see — “parks that were inviting to a diverse range of residents,” to name one. The crux of their proposal, according to Rojas and Kamp, is that traditional community engagement rewards people who have the time and skill to develop oral arguments and who have mastered the language of planners. The book quotes one transportation planner as saying that “the general town-hall-meeting format” causes people to “double down once they have stated their opinion and it’s been affirmed by others.” By comparison, building models and exploring places lead to consensus on shared experiences — rather than a gradual surrender to the loudest opinions. In many ways, Dream Play Build asks planners to think like activists — advocating and building consensus for a planning solution — rather than as planners forced to defend a side in tense community fights.

Whereas community engagement may deal with the tools that are needed (to consider infrastructure, for example), the Dream Play Build approach focuses on solutions the community wants to see — “parks that were inviting to a diverse range of residents,” to name one. The crux of their proposal, according to Rojas and Kamp, is that traditional community engagement rewards people who have the time and skill to develop oral arguments and who have mastered the language of planners. The book quotes one transportation planner as saying that “the general town-hall-meeting format” causes people to “double down once they have stated their opinion and it’s been affirmed by others.” By comparison, building models and exploring places lead to consensus on shared experiences — rather than a gradual surrender to the loudest opinions. In many ways, Dream Play Build asks planners to think like activists — advocating and building consensus for a planning solution — rather than as planners forced to defend a side in tense community fights.

This is a radical approach, to be sure. For many of its readers who are professionals, 170 pages may not be enough to convince them to throw out years of engagement practice. Two pages of notes cover Chapters 1 through 5. A deeper bibliography, with more examples to help practitioners, would help to onboard them to Rojas’ and Kamp’s process.

In addition, and perhaps befitting the book’s “Play More, Talk Less” approach, suggestions for online engagement would be helpful. The book criticizes online-first engagement practices, exacerbated, they say, by algorithms that thrive on polarizing communities. It would perhaps have been better to recognize that many jurisdictions require their planners to drive engagement not just in person, but on their laptops and phones as well, and make recommendations accordingly.

“Trust” appears only 11 times in this book, yet it seems to be an underlying theme. If planners trust the communities in which they work — and are “less deterministic and prescriptive,” as voiced by a practitioner in South Colton — the communities will see glimpses of the future they want. Trust begets trust, and by opening engagement to the hands and the senses instead of only to the loudest voices, Dream Play Build proposes a revolution — not just in how community engagement is undertaken, but in the set of skills required to engage those most affected.

This revolution is intimidating. But in fixing a broken system, it may be planners who ought to be intimidated, not the public.

Asher Kohn, AICP, is a Planner with M-Group. He holds a master’s in city/urban, community and regional planning from the University of Illinois (Chicago), a JD from Washington University (St. Louis), and a BA in history from the University of Maryland. You can reach him at asherj.kohn@gmail.com.

Asher Kohn, AICP, is a Planner with M-Group. He holds a master’s in city/urban, community and regional planning from the University of Illinois (Chicago), a JD from Washington University (St. Louis), and a BA in history from the University of Maryland. You can reach him at asherj.kohn@gmail.com.