Creating a Sustainable Urban Development Plan for the Greater Banjul Area, The Gambia

By Holly Pearson, AICP

I remember the precise moment I realized I had to unlearn all my expertise, everything I thought was the right way to approach an urban planning exercise. It was about two months into my contract as a senior urban planning analyst with the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), working with a team of planners and engineers to synthesize background research and stakeholder input into a comprehensive plan for the Greater Banjul Area (GBA), capital city region of The Gambia in West Africa. I had been hired for the project based on my years of experience with comprehensive planning in the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as a few international planning projects I had worked on in Latin America with Ecocity Builders.

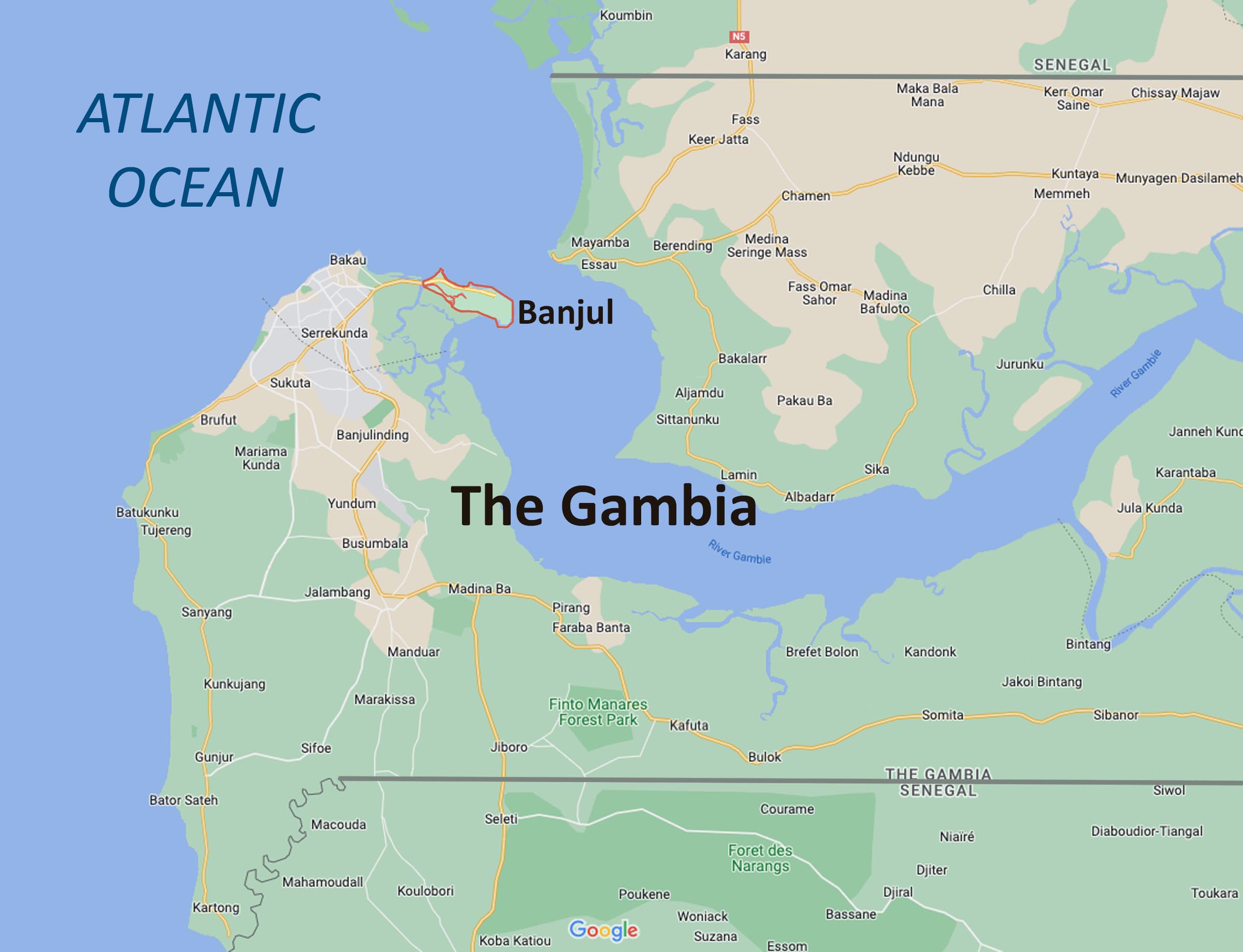

In October 2021, I was on an official UN mission to the Banjul area. The Gambia, which carves out from Senegal a narrow sliver of land following the boundaries of the Gambia River watershed, has a current population of just over 2.5 million — roughly equivalent to the combined population of San Francisco and Alameda Counties. The capital city region, consisting of the municipalities of Banjul, Kanifing, and Brikama, plus a handful of smaller communities and villages, is home to 55 percent of the country’s population.

Like many African city-regions, the GBA is urbanizing rapidly, and much of the development is informal and unplanned. The goal of our UNOPS project was to prepare a sustainable urban development plan for the GBA that addressed the numerous challenges facing the region. These include major land use conflicts between the Port of Banjul and the adjacent urban core of the capital city, poor infrastructure, unregulated development, insufficient housing supply, informal settlements, loss of agricultural and open space lands, environmental degradation, and local climate change impacts.

My epiphany occurred during a stakeholder workshop with officials from national and local governments, the Port, tribal leaders, utility companies, and other key groups. I had prepared my part of our presentation on the existing draft policy framework for the GBA Development Plan, which included a point about strengthening both the process and regulatory context for review of proposed new development projects and the capacity of the local governments to carry out these reviews. My UNOPS colleague, Talía Rangil Escribano, who had been based in The Gambia working on the project for a little over a year, pulled me aside. “It’s not the local governments that issue approvals for development projects,” she whispered. “It’s DPPH,” the Department of Physical Planning and Housing.

I looked back at my slides, thinking on my feet about how I could quickly edit my presentation. DPPH is a division of the national Ministry of Lands and Regional Government. I suddenly felt a bit embarrassed about my error and my lack of familiarity with the structure and roles of government entities in The Gambia. But that moment didn’t just prompt a literal step back to think about how to revise my talk for that day’s workshop — it also prompted a big metaphorical step back from all my knowledge, all my assumptions, all my biases — formed by my education and my work experience in the wealthy, powerful, and orderly countries of North America. It suddenly hit me with the force of a Gambian monsoon storm — I didn’t really understand anything about how things worked in this small West African nation.

I am no stranger to unfamiliar political contexts or rough conditions in less developed parts of the world. My passion for travel and cross-cultural experience has taken me to some three dozen countries on six continents. Yet somehow none of my previous international travel, study, or work experience had quite prepared me for The Gambia. Known as the “Smiling Coast of Africa,” The Gambia is rustic, friendly, and rich in its culture and biodiversity. It is considered a low-income country, ranking number 172 out of 189 countries worldwide in terms of the UN Human Development Index. My brief time there was profoundly eye-opening in many respects.

I had already read the statistics as part of the preparatory work for the development plan: nearly 27 percent of households in the GBA do not have piped water and nearly 32 percent lack proper sanitation service. Yet during a day-long reconnaissance tour around the GBA with my UN colleagues, I was surprised and fascinated by what I observed. Outside of the old capital city of Banjul, most of the roads in this region of 1.4 million people (except for the major highways) are unpaved.

My visit coincided with the end of the rainy season, and in the city of Brikama (pop. 731,000 in 2013) and other parts of the southern end of the GBA, many city streets lack drainage infrastructure and were inundated with water. Bicycles, tuk-tuks, taxis, donkey carts, and pedestrians crisscrossed through the muddy water. Outside the Brikama branch office of the DPPH, a small herd of goats grazed the overgrown vegetation next to a heap of abandoned, rusted, old cars. At a small home-based childcare facility on the outskirts of Brikama where we made a brief stop, there was no running water.

In the heart of old Banjul, next to the massive seaport, warehousing and logistics facilities have encroached into residential areas, and freight trucks lined the city streets — there were no apparent rules or regulations for truck parking. Along the main north-south commercial thoroughfare that connects Banjul, Kanifing (pop. 323,000 in 2003), and Brikama, informal businesses encroach into the public right-of-way, competing for space with pedestrians and traffic. The main form of ‘public’ transportation is privately owned vans and minibuses that circulate through the city picking up and dropping off passengers. The “system” is highly efficient but completely unregulated, with no safety standards and no checks or authorizations required for vehicles or drivers. The region’s sole formal solid waste disposal facility, the Bakoteh landfill, is located in the heart of Kanifing, surrounded by residences, and bordering a large creek.

During my stay in The Gambia, I was told an amusing story by our UNOPS programme director, Agathe, about a discussion she had with a potential donor agency from the European Union. Agathe is a French urban planner with experience in several countries who aptly describes herself as a “planner for unplanned places.” The EU donor group had approached her about their interest in investing in a bus rapid transit system for the GBA — a flashy project featuring the newest, greenest, transportation technology. “I just had to turn my head aside slightly and laugh,” Agathe recalled. “I told them, ‘Perhaps you don’t realize that most of the roads aren’t even paved.’”

For me, that anecdote about the well-intentioned yet misguided EU donors came to embody what often happens when planners, engineers, economists, and other professionals from the Global North engage in urban sustainability work in the Global South. Once I humbly admitted to myself that I didn’t really understand anything about how to plan a city in The Gambia, I began relying heavily on the expertise and advice of my two Gambian counterparts, my planning team colleagues Felicia and Madiba. I asked them endless questions: What government entity is responsible for this? What is the procedure to accomplish such and such? What is the legal context in The Gambia for XYZ? They answered my questions and pointed me to relevant legislation, which I studied in exhaustive detail. And then I went back to Felicia and Madiba, puzzled: “So I read through the regulations for development control that are on the books. Why aren’t they enforced?”

That was the one question that no one could answer.

Back in the United States, I sought advice from an old friend who worked for many years with the US Agency for International Development, promoting democracy and governance initiatives in post-conflict places like Rwanda and Afghanistan. “Tye,” I said, “I want to write the policy chapter of this plan to be very simple — not to try to take on every challenge, but just to facilitate the government authorities really moving the needle on a few of the most critical issues. But how do I write a plan and an implementation strategy that they will follow and use, given the government’s inertia and the entrenched practice of weak enforcement?” Tye nodded with understanding, then offered, “What if you didn’t try to figure out how to change the public institutions and practices to be more effective, but rather used as your starting point the assumption that things aren’t going to work as intended? That the government systems won’t be strong and efficient?”

Tye’s suggestion set me into motion to fundamentally rethink my approach to the GBA development plan. Chaos, informality, and lawlessness were not likely going away anytime soon. My job was to figure out how to get those dynamics to work in favor of sustainable outcomes instead of against them. I realized the need to simplify the plan’s approach and build on things that are already working in the GBA (no matter how confusing and disorderly they might seem to my “first-world planner” mind).

In March 2022, my UNOPS colleagues and I delivered the final Greater Banjul Area 2040 Development Plan to the Gambian Ministry of Lands and Regional Government for formal adoption, along with a roadmap for implementation of the plan. As our team wrapped up the project and reported on its outcomes to our funder, the African Development Bank, I felt proud of what we had accomplished and cautiously hopeful about the future of the GBA region. Most of all, I was profoundly aware and appreciative of how the experience of planning for a West African city had shifted my professional perspective and opened my worldview.

Holly Pearson, AICP, is an independent planning consultant working on international initiatives and projects in northern California. From 2007 through 2015, she was a planner for the cities of Oakland and San Francisco, and from 2014 through 2021, she worked for Ecocity Builders and Michael Baker International.

Holly Pearson, AICP, is an independent planning consultant working on international initiatives and projects in northern California. From 2007 through 2015, she was a planner for the cities of Oakland and San Francisco, and from 2014 through 2021, she worked for Ecocity Builders and Michael Baker International.