By Patrick Sisson – Aug. 17, 2023 – This article is reused with permission from the American Planning Association copyright 2023.

Acquiring the skills of foresight and futures literacy helps planners to confidently prepare for an uncertain tomorrow.

INNOVATIONS THE PROFESSION

Illustration: iStock by Getty Images.

For a powerful example of how the future is often unexpected, consider the smartphone. When these devices first became popular in the mid-2000s, few planners (or others, for that matter) had the foresight and imagination to realize that within a decade, mobile computing would send our cities in a whole new direction.

Think about it: what was once a simple communication device has revolutionized urban transportation through ridesharing and micromobility, housing (Airbnb), and gig work. One technology unlocked a series of changes and consequences for cities.

Planners, traditionally focused on the changes their plans and policies guide, often don’t fully anticipate how shifts happening in the world around them can significantly affect their communities.

But maybe they need to start.

This smartphone example comes from Petra Hurtado, PhD, director of research and foresight at the American Planning Association (APA). It showcases the ways that what’s inconceivable today could become commonplace — and perhaps highly disruptive — tomorrow. Hurtado’s work seeks to bring what’s called futures literacy to the planning profession.

Planners might argue that their work already focuses on the future. But traditional plans are based on existing data, the patterns of the past, and the assumptions of today. That means they are, by definition, reactive. Hurtado’s key insight is that planners need to become comfortable with making plans that are less prescriptive. Planning work — and indeed the profession itself — needs to recalibrate its focus to agility and preparedness for multiple possible futures, as well as on developing the infrastructure needed to be resilient in the face of whatever comes.

“Even though we make plans for the future, we don’t always consider the future —

or better, multiple plausible futures — in our plans, which is a big issue.”

“Even though we make plans for the future, we don’t always consider the future — or better, multiple plausible futures — in our plans, which is a big issue,” says Hurtado.

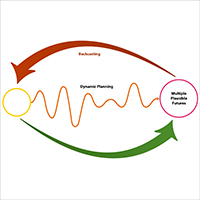

Planners can acquire the skill of futures literacy and a mindset that, while no one can predict the future, we can prepare for it by combining hindsight, insight, and foresight.

What is futures literacy?

In an era of rapid economic, technological, and demographic shifts, buffeted and catalyzed by climate change, planners need to adopt a more forward-thinking approach to their work, one that can rapidly evolve and adapt.

Futures literacy is “the skill that allows people to better understand the role of the future in what they see and do,” according to UNESCO, which calls futures literacy a key 21st-century skill. “Being futures literate empowers the imagination, enhances our ability to prepare, recover, and invent as changes occur.” APA, through its Upskilling Initiative, has also identified futures literacy as an important skill for planners as they address the challenges and opportunities of a changing and uncertain world.

Developing futures literacy will help planners make sense of the future, understand drivers of change that are outside of one’s control, and prepare for what may lead to success or failure, says Hurtado. It can also help planners be “comfortable with — and even confident about — uncertainty,” she adds.

The concept of futures thinking and related foresight practices initially emerged during the post-WWII period. The concept of strategic foresight was initially embraced by Cold War military planners seeking to game out potential conflicts and de-escalate during the era of superpower conflict.

Soon, the methodology would make its way to corporate America, where leaders sought to future-proof products, business strategies, and their companies, and get a better sense of shifting consumer sentiment. It’s since been adopted by myriad organizations, including UNESCO, which is working to integrate futures literacy into school curricula.

Planning with foresight

Now futures literacy has come to the planning profession, and Hurtado and other proponents suggest planners adopt a series of concepts and methodologies in their work. She calls this practicing foresight, which starts with the future and then reverse engineers what needs to happen today to get to the most desirable outcome. This is different from visioning, which starts with the present and creates goals for the future.

Practicing foresight starts with the future and then reverse engineers

what needs to happen today to get to the most desirable outcome.

“Local governments are a perfect place for foresight,” agrees author and professional futurist Rebecca Ryan, who often consults with cities on long-range planning. “If you start your foresight project for a city based on historical numbers, at best, you’re going to get a rinse-and-repeat of your current outcomes. And [worst], you’re going to be completely flat-footed for any disruption. Just a one-percent change, compounded over 20 years, can be huge.” There are multiple approaches and methodologies to practicing foresight. (The Future: A Very Short Introduction by Jennifer Gidley is a good resource on the history of foresight, futures studies, and futures literacy.)

The most important components when planning with foresight, and the most relevant to planning are:

- Trend scanning: researching existing, emerging, and potential future trends (including societal, technological, environmental, economic, and political trends, or STEEP) and related drivers of change

- Signal sensing: identifying developments in the far future and in adjacent fields outside of the conventional planning space that might impact planning

- Forecasting: estimating future trends

- Sense making: connecting trends and signals to planning to explore how they will impact cities, communities, and the way planners do their work

- Scenario planning: creating multiple plausible futures

- Backcasting: understanding what needs to happen today to be prepared for multiple plausible futures

Adopting this kind of strategic foresight should encourage local planning agencies to move from innovating as a response to a crisis to innovating because it’s an ingrained part of organizational culture. That also implies that creativity and openness to new ideas are also key to success.

“I do believe that if we want to shape the future, we also need to be able to imagine it. This is about institutionalizing imagination as a very powerful planning tool,” Hurtado says.

Also critical is the incorporation of many diverse perspectives into the process. Engaging the community — and every facet of the community — strengthens the results.

Resources for Foresight Planning

Planners can tap into APA resources on foresight planning, including guides on the process, courses on using the future to create dynamic plans, reports on climate-focused uses of these methodologies, and an expanding library of additional resources.

“By inviting people into this conversation to look at the challenging things that could go wrong, they realize that inaction is not an option,” Ryan says. “That’s important in a political environment. Very often, with these really wicked problems, we just kick the can down the road.”

Exploratory scenario planning (XSP) can be a particularly useful tool in foresight work because it helps create possible alternative futures. “The methods are based on an open-ended, qualitative exercise of conducting research and brainstorming about the forces that are going to shape the future of what we’re planning,” says Robert Goodspeed, AICP, an associate professor at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning.

The Twin Cities, Minneapolis and St. Paul, used scenario planning in the Metropolitan Council’s 2050 regional planning process, which Hurtado commended for pushing through local policy changes. These exercises can create powerful civic visions that help coalesce political support and achieve clarity around policy.

Trend Scanning

Part of foresight practice is becoming knowledgeable about current and emerging drivers of change. Some of the trend scanning that planners may need is already being done. Hurtado and her team meet quarterly with the Trend Scouting Foresight Community, a group of experts and leading thinkers from numerous disciplines. Their work is compiled annually in the Trend Report for Planners, in partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Planners need to evaluate trends based on their certainty and the effect they are likely to have, then prioritize which ones deserve more focus. That approach invites planners to focus on a range of outcomes, as opposed to only planning for one future and hoping everything works out.

Take the emerging trend of urban air mobility, which might get rated as high-certainty and high-impact in big cities, where this technology is already being tested. (The FAA plans to allow flying taxis by 2028.) Planners in those cities may want to start preparing for how to equitably and sustainably integrate these emerging systems into the existing transportation network. However, for a rural community this technology might get rated as low-certainty and medium-impact. In those areas, a topic like lab-made meat might get more attention.

Illustration by iStock by Getty Images – Drazan

Foresight in action

In Calgary, Alberta, the city government has been using strategic foresight for nearly a decade, catalyzed by a catastrophic regional flood in 2013. This weather event made clear to the planning team that they needed to be nimbler and more resilient.

In Calgary’s approach, the process starts with a core team that scans for trends and produces internal research. Those results get filtered through all city departments to assist with planning that is innovative and tech-focused, as well as “agile to emerging stresses, shocks, and opportunities,” according to the Future-focused Calgary website.

Strategic foresight has helped influence all aspects of city planning there — including economic development and post-COVID transportation plans — with a particular focus on adapting to shifts toward digitalization, preparing for climate change, and reinforcing trust in government. There’s even a report assessing the top trends for 2035.

“For economic development, this allows us to make sure we have the people skills and educational attainment we need,” says Heather Galbraith, Calgary’s strategic foresight program lead. Whereas the team used to think, “we’ll figure it out as long as we get the businesses to come here,” she says, “this new process allows us to really interrogate our strategies and have mechanisms in place to make sure we have what’s needed to be successful in the future.”

Planning may be criticized for rigidity, or trying to create a sense of certainty when cities require agility and dynamism. Planners can respond by building more flexibility into their long-range planning, Hurtado argues, providing mechanisms and milestones within plans that allow for pivots and rapid shifts depending on the changing world.

Planning departments may view this as a daunting task, but Hurtado recommends that departments of any size consult existing resources, including APA’s work on foresight and the Trend Reports for Planners. These approaches aren’t about bold predictions or seeing black swan events before others. They are a means to get comfortable with change and be prepared for uncertainty.

“There’s no right or wrong,” says Hurtado. “It’s a very humble type of work, because next year, everything may change.”

Patrick Sisson is a Los Angeles–based writer and reporter focused on the tech, trends, and policies that shape cities.