By Al Savay, AICP.

RETHINKING SINGLE FAMILY HOUSE SIZE.

The single-family detached house is an icon — a symbol of the American Dream. Owning a single-family home is the culmination of hard work, financial planning, risk, strategic thinking, and sacrifice.

Demographic changes have revealed major shifts in how our country views home ownership. Even so, middle-class or millennial, many still plan their lives around owning a single-family home. If we are fortunate enough to make it into the ownership circle, we inevitably develop very strong feelings about what our neighborhood should look and feel like, and what’s appropriate in terms of house size and scale. We’re likely to decide that the neighborhood should stay the same as when we bought there, and that our neighbors should also resist change.

American cities have embraced the notion of the suburban neighborhood as an inviolable place by adopting building and lot standards to ensure a distinct scale, proportion, and character. Thousands of public-sector planners started their careers at the zoning counter, reviewing additions and “remodels” of single-family homes against those standards. Any planner who has worked the zoning counter knows that getting in the way of owners who want to add to, or rebuild, their houses is a recipe for high blood pressure for both parties.

This is the story of one city’s assessment of what is fair and appropriate in terms of single-family house size and scale.

The setting

San Carlos is a city of 30,000 in southeastern San Mateo County, with 8,000 properties zoned for single-family residences.

As the fortunes of Silicon Valley led to high-paying jobs, stock options, and bonuses, our community became a very desirable place because of its central Bay Area location, sense of community, and top-performing schools. An influx of young, two-income households have come to raise their families in San Carlos. Much of the single-family housing stock had not been touched since the 1950s.

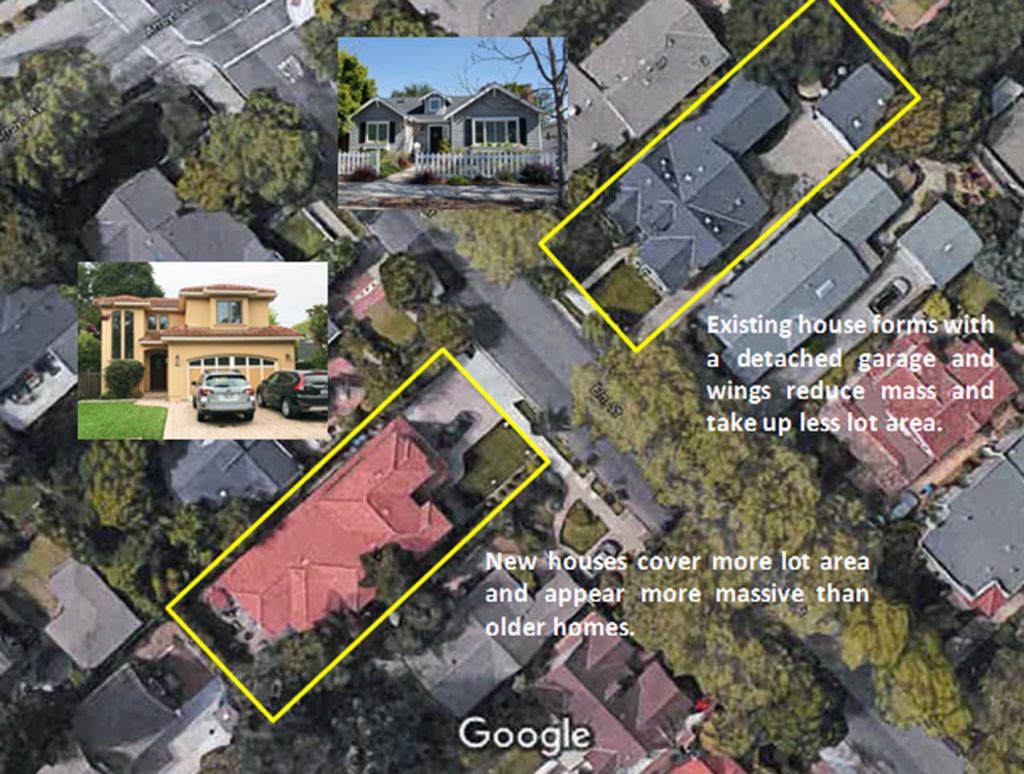

These new buyers began hiring local architects, designers, and contractors who relayed to city staff that the first question from their clients was, “How much house can I build?” Their needs and desires differ from those of long-time residents. In addition to a minimum of three bedrooms and two baths — or even more for multi-generational families — they want higher ceilings, mudrooms, open floor plans with combined kitchen and family rooms, media rooms, and an office or two. All of this led to larger, taller houses, many of them on the original, small, narrow lots next to smaller, one-story homes.

The planner’s task in leading a change in how much house one can build is fraught with challenges. This is where zoning directly intersects with “home,” the most fundamental and personal space in the American psyche. There can be no straightforward answers or recommendations from city officials, no matter how well thought out. No matter how empathetic, the proposals are sure to meet with criticism and scorn.

In 2016, the San Carlos City Council held study sessions in response to community concerns about the size of new homes and additions. Community members complained about a proliferation of “monster homes” and “McMansions” that compromised their light, solar access, air and privacy, particularly on blocks where most homes were single-story. To some, these larger homes were unnecessary. Hadn’t they successfully raised their families in much smaller houses? Others complained their privacy was being eliminated by the second stories that loomed over their backyards.

The city council directed its planners to study these complaints and recommend changes to single-family house-size standards. A Community Coalition formed around the issue and began presenting ideas on how to solve the problem, positing Floor Area Ratio and Daylight Plane as solutions.

To democratize the process, the planners recommended that the council appoint a citizens advisory committee of local stakeholders to work collaboratively with city staff and an urban design consultant. A seven member Citizens Advisory Committee — four single-family property owners, a local builder/developer, a local architect, and local residential realtor — were appointed to evaluate, guide, and recommend new standards.

Discovery and idea phase

We started the process with ideas for successful outcomes:

- How can zoning standards and design address negative impacts from “inappropriate” house size?

- What are some directions and options for better massing?

- Is it possible to develop a more consistent overall design, look, and feel?

- Can a context-sensitive approach to the site and its surrounding homes be considered?

- How can misunderstandings between neighbors about house size be addressed?

We reviewed the existing code, evaluated building forms, geography and topography, permit data, and peer city standards. These issues emerged:

- The city did not have a Floor Area Ratio (FAR) — the ratio of the total floor area of a building to its lot area. Most peer cities used FAR as the primary limiting factor for house size.

- Our existing standards allowed too much bulk at the front and sides of the house.

- Upper floor setbacks were somewhat ineffective in reducing upper floor mass.

- Our front and rear setbacks resulted in very long houses.

- Two-car garages dominated about 65 percent of the house front, accentuating the bulky appearance from the street and making living areas and entries secondary.

- The majority of the single-family lots in San Carlos were relatively narrower and smaller than in neighboring cities.

A Form Based approach

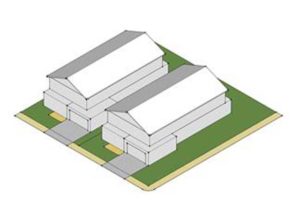

We found no single solution to address house size and bulk. Floor Area Ratio seemed like a logical limiting factor, a “no brainer.” FAR reduces overall square footage, but it does not address either the overall physical form of a house or how it looks in the context of other homes on a given block. And FAR appears not to reduce the apparent size of a home where it counts — along the street frontage, or at the rear as seen from a neighbor’s backyard.

Many communities have crafted regulations that fit with the character of their neighborhoods. Very few Bay Area cities apply a Form Based approach to single-family homes. Those that do are satisfied with the results.

In 2017, the Citizens Advisory Committee held six public meetings with city staff and the consultant. The committee focused on which features of a home’s design make them look large or out of scale, and which features seem to work.

The committee reviewed various approaches, including FAR, to reduce house bulk and mass, and discussed how to manage house size and scale in the context of surrounding homes. It became clear that a set of coordinated design solutions would be needed to effectively address the physical form of the house and reduce its apparent bulk and mass.

Key ideas

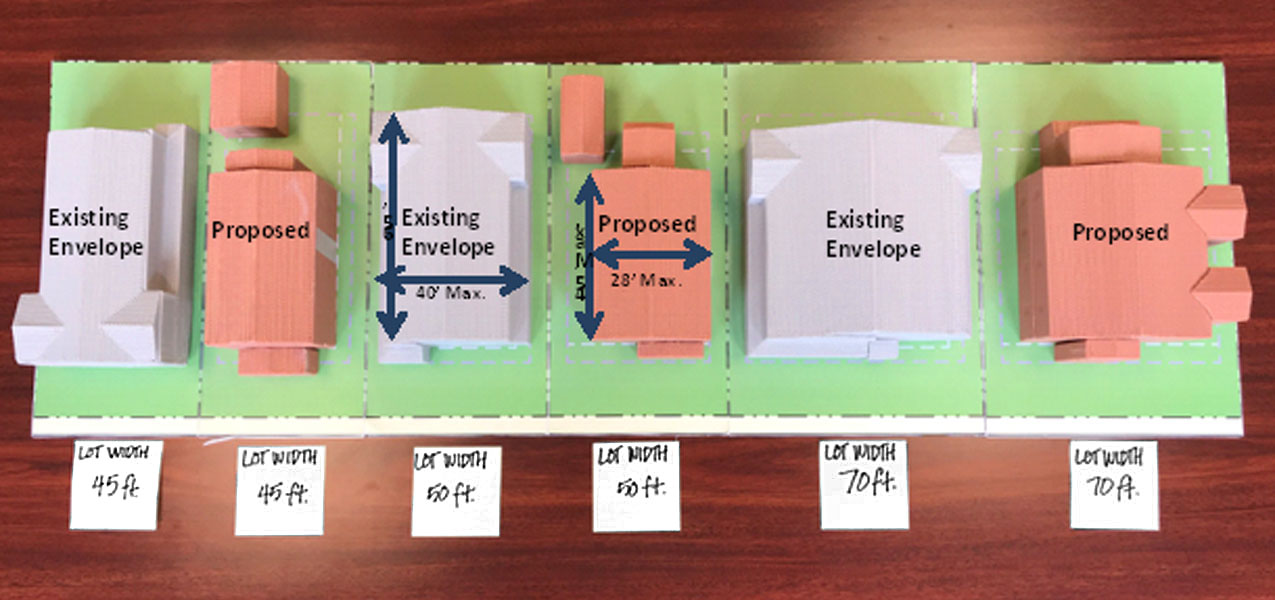

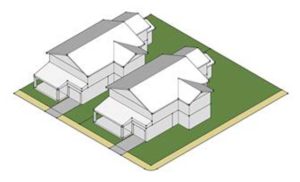

To address the issues identified by the community, while not unfairly penalizing those who want to add floor area, the Citizens Advisory Committee recommended a Form Based approach with no FAR limit. For controlling bulk and mass and respecting neighborhood context, FAR was seen as an arbitrary standard and less effective than the Form Based concept. In general, building appearance, scale, and massing could be mitigated more successfully by controlling the structure’s width and depth. This would produce a house form that more closely mirrors existing houses, especially with respect to scale and backyard privacy. And it would reduce overall floor area by 30 percent compared to our existing standards.

The recommended Form Based standards included:

- New controls over main building size and bulk

- Allowing wings to be added to the main body to gain square footage

- Incentives for garages placed in the middle and rear of the lot

- Greater rear-yard and upper-floor setbacks

- A sliding scale for lot coverage based on lot width

- One covered parking space and one car uncovered space in driveways on lots less than 60 feet wide

- Improved procedures, definitions and design review criteria

- The ideas were then presented to the community, local architects, and designers, and at several Planning Commission study sessions.

Here is a summary of what we heard back:

- The proposed standards don’t go far enough

- The process is moving too quickly/too slowly

- New standards should match those of other cities; these ideas do not limit square footage as much as some other cities do

- The ideas don’t protect a neighbor’s light, views, and privacy

- Local architects believe the recommendations won’t reduce house size

- Use FAR limits in line with what peer cities use

- Establish a 50 percent lot coverage and require a solar study

Sometimes you need to pivot

At about the same time the public meetings were taking place, a number of other significant issues arose: Three of five planning commissioners termed out, and three of five city council members would change seats in a few months’ time. The sitting city council had been extensively engaged in the process and had a strong grasp of the issues and the recommended solutions. Getting a newly elected city council up to speed on the complexities of the code changes was not ideal. The process had already taken 18 months, and pressure was building to wrap it up.

Planning staff went to work educating new commissioners about Citizens Advisory Committee recommendations and options and community concerns. Over the course of several planning commission hearings, the merit of the Form Based ideas was acknowledged. But there was very little community support and the Community Coalition demanded a deeper reduction in square footage than the 30 percent the Form Based approach would achieve. As the time for city council turnover approached, the commission was at an impasse and asked for other solutions including FAR based standards.

Planning staff delivered several FAR options with a mix of some Form Based components that seemed to have planning commission support. Following a late night hearing, one commissioner approached me and said, “Just when I think we’ve hit a wall, you always seem to find us a way out.”

Where we ended up

After our in-depth consideration of the Form Based approach, it was clear to us, the city planners, that it was a superior solution that addressed community issues by reducing the size, massing, and appearance of new homes and additions. That said, we are not the decision makers, and our duty as facilitators takes precedence. That led to what we believe will be an effective solution to the house-size issue in our community.

The planning commission recommended a robust set of code changes a month or two before the new city council was seated. In November 2018, the Council refined the Commission’s recommendations and adopted a new set of rules combining a sliding scale maximum FAR with some of the Form Based ideas.

More recently, the Community Coalition asked the new city council to revisit the recently adopted standards. In their view, the new standards do not go far enough.

Albert Savay, AICP, is the Community & Economic Development Director of the City of San Carlos. He is Chair of the Bay Area Planning Directors Association (BAPDA) and sits on the ABAG Regional Planning Committee. You can reach him at asavay@cityofsancarlos.org

Albert Savay, AICP, is the Community & Economic Development Director of the City of San Carlos. He is Chair of the Bay Area Planning Directors Association (BAPDA) and sits on the ABAG Regional Planning Committee. You can reach him at asavay@cityofsancarlos.org