Samuel Herzberg, AICP.

TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS AGO, an expedition led by Gaspar de Portolá travelled 1,200 miles up the Alta California coast to explore an overland route for establishing Spanish harbors at San Diego and Monterey Bay. Following well-established footpaths that marked trade routes between native villages, the expedition traveled farther north, and its members became the first Europeans to see the San Francisco Bay.

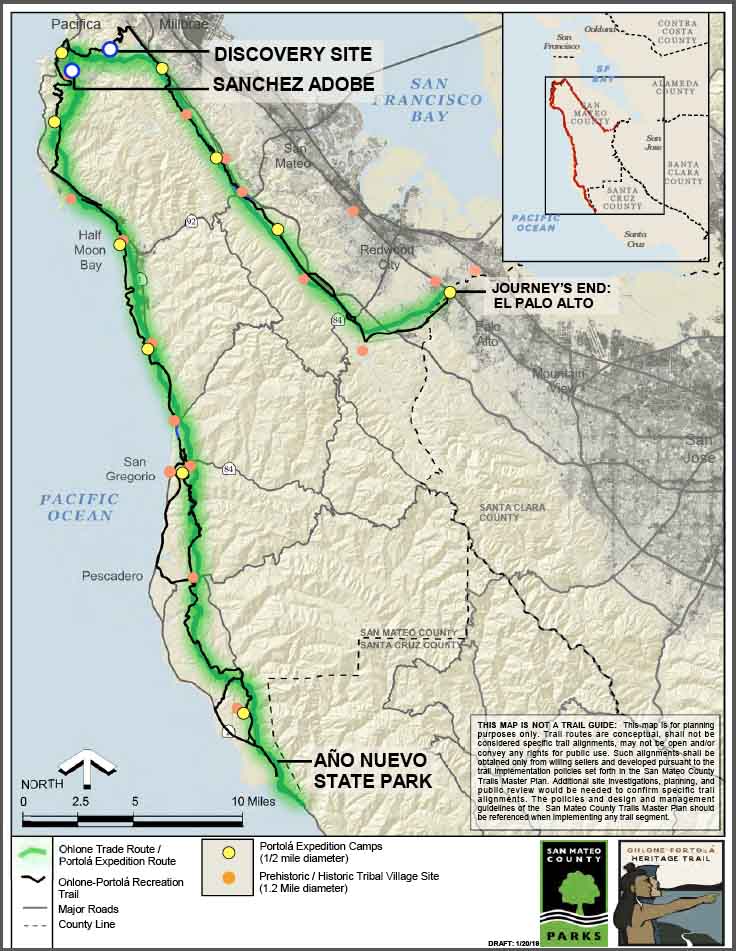

Portolá himself, Father Juan Crespi, and Miguel Constansó — the party’s engineer — chronicled the expedition. According to surviving journals, the expedition did not recognize Monterey Bay from Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno’s 167-year-old description and so continued north, in search of a suitable harbor. As the expedition entered what is now San Mateo County near Año Nuevo State Park, they were welcomed by the Quiroste people at one of the larger villages along the coast.

The Quiroste provided much-needed nourishment to Portolá’s men, reviving the scurvy-ridden soldiers, and told them of two harbors about three days’ walk north. Their guides led the Portolá party to neighboring villages at San Gregorio, Tunitas Creek, and Half Moon Bay. At Montara Mountain, Costansó recognized the farallones to the west, — a group of islands 20 miles outside the Golden Gate and a known landmark even in those times — and realized they had passed Monterey Bay. Atop the mountain, they met a group of about 25 Aramai, who may have been from the village of Pruristac in Pacifica where the Sanchez Adobe now stands.

As the party camped nearby in San Pedro Valley, a small group went up the hills to hunt deer. They came back after nightfall describing a giant estuary surrounded by smoke from the fires of native villages. These hunters became the first recorded Europeans to see what we now call San Francisco Bay, most likely from somewhere atop what is now known as Sweeney Ridge. November 4 will mark the 250th anniversary of this historic and unexpected experience.

The Expedition continued south through the Crystal Springs Watershed towards Woodside, and then east, ending at the north (Menlo Park) side of San Francisquito Creek. The Menlo Park camp was adjacent to the El Palo Alto tree from which the city of Palo Alto takes its name. At the end of their route, the party followed their path back through San Mateo County and along the California coast, returning to Baja California and then to Spain to report on their findings.

HISTORIANS ESTIMATE that indigenous people have lived for approximately 10,000 years in what is today San Mateo County. Natives — the Ramaytush Ohlone, who shared a dialect — numbered more than 2,000 in the area in 1769. They were generally organized in territories bounded by watersheds, with small groups living in villages spaced three to five miles apart along the creeks and valley. The subsistence and material culture of the Ramaytush Ohlone did not differ from other neighboring Ohlone societies. (“Ohlone” encompasses 50 Bay Area tribes that had a common root language.)

Local Ohlone culture was cosmopolitan, much as the San Francisco Bay Area is today. The Ohlone harvested plant, fish, and animal resources from the environment and acquired additional resources through extensive trade networks, including some that extended across the San Francisco Bay to the north and east.

At the time of the Portolá Expedition, California had the densest population of indigenous people north of Mexico: More than 300,000 lived here — more than all the Indians of the Great Plains — with the largest concentrations in the Sacramento Delta, the Santa Barbara area, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

With Measure K funding — a countywide half-cent sales tax extension passed by county voters in November 2016 — the San Mateo County Parks Department prepared a feasibility study for a 90-mile interpretive, multi-use, recreational trail (and a future auto route) through the county to commemorate native and Portolá history and honor the region’s native culture. The trail will follow Native American villages, the adjacent Portola Expedition camps, and the trade routes connecting villages. It will be the first trail to connect the coast to the Bay.

Utilizing existing regional alignments, the trail route is already half complete; it needs to be signed. Future sections will largely use public lands of San Mateo County Parks, Peninsula Open Space Trust, CalTrans, Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, State Parks, San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and the Golden Gate Recreation Area. Interpretive signage will tell the story of the indigenous Ohlone culture, the Portolá Expedition’s 27 days in San Mateo County in 1769, and U.S. West Coast history.

All of the Portolá Expedition camps are already designated State Historic Landmarks. The Ohlone-Portolá Heritage Trail connects them. The San Mateo County Historical Association is nominating the trail to the State Office of Historic Preservation as a State Historic Trail. The County has funded a documentary film that will screen at a new Interpretive Center at the Sanchez Adobe. Both will open in Pacifica October 26, 2019.

Seven years after the Portolá Expedition, the Juan Bautista De Anza Expedition led to the missions being developed in California. The Juan Bautista De Anza Trail is a designated National Historic Trail.

You can see the Ohlone-Portolá Trail Feasibility Study on the San Mateo County Parks Department web page.

Samuel (Sam) Herzberg AICP, holds a master in urban planning from San Jose State University and a B.A. in geography from San Francisco State University. For 20 years, he has been a member of APA and an employee of the San Mateo County Parks Department, where he is a senior planner. Herzberg is a member of the Indicators Committee of Sustainable San Mateo County, where he helps oversee and manage quarterly updates of indicators.

Samuel (Sam) Herzberg AICP, holds a master in urban planning from San Jose State University and a B.A. in geography from San Francisco State University. For 20 years, he has been a member of APA and an employee of the San Mateo County Parks Department, where he is a senior planner. Herzberg is a member of the Indicators Committee of Sustainable San Mateo County, where he helps oversee and manage quarterly updates of indicators.